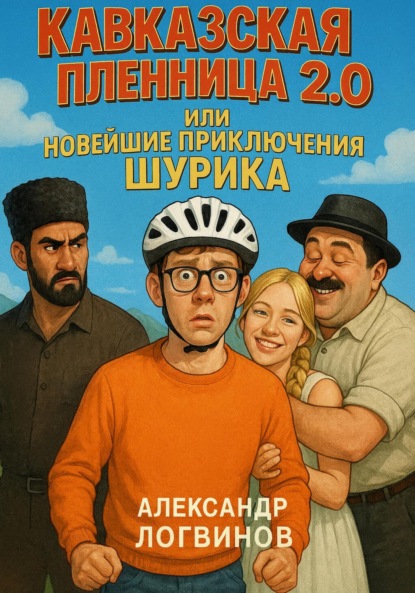

The Caucasian Captive 2.0, or The New Adventures of Shurik

- -

- 100%

- +

Chapter 1. In the Mountains

High in the mountains sprawled a small aul—a settlement seemingly clinging to the slope. Stone houses stood in tiers: the roof of the lower one served as a courtyard for the one above. The morning sun gilded the snowy peaks far above, and below, in the valley, a turbulent river wound its way. The air was fresh and clear—one could breathe it deeply. A traveler named Shurik stood at the entrance to the aul, admiring this view, and felt his heart happily pounding in anticipation of adventures.

Shurik was a young researcher—an ethnographer who had come to study the customs and folklore of the mountain peoples of the Caucasus. He carried a light backpack, and a camera hung around his neck. He was inquisitive and observant, like a true detective. Even now, standing on the path, Shurik noticed details: behind one of the houses, a woman was spreading fruits on the flat roof—to dry them in the sun. By the neighboring wall, bundles of herbs—thyme and St. John’s wort—hung from a rope, a supply for tea and medicine. Chickens ran around the yard, and a cat dozed on the crossbar of a fence.

Children were coming towards Shurik along a narrow lane. Two boys about six years old were leading a little donkey laden with bundles of firewood. The kids were chatting merrily and even skipping a little as they walked. One youngster boldly leaped onto the donkey from behind and rode it for a few meters, spreading his arms out to the sides. Shurik smiled: here in the mountains, children start riding horseback before they can even walk, as he had read in books. A girl with braids was carrying a basket from which peeked red apples and fresh lavash—a round flatbread. Noticing the guest, the children stopped and stared at Shurik with large dark eyes full of curiosity.

“Hello!” Shurik said in a friendly tone, waving to the kids.

The children greeted him and immediately started asking questions: who was he, where did he come from? Shurik explained that he came from a big city to get to know their land. The boys exchanged glances: a guest from far away—this was important.

“My uncle said a scholar from the city would arrive today,” the girl said. “That must be you, right?”

Shurik nodded. The children happily bobbed their heads, pleased with their guess.

“Come on, we’ll show you the way,” the older boy suggested. “All the houses here are mixed up; you might get lost.”

Shurik thanked them and followed the little guides. They led him along a winding lane paved with flat stones. The houses stood so close to each other that the roofs almost touched. Some walls were decorated with beautiful ornaments—carved wooden panels. Shurik noted to himself that each pattern surely had its own meaning and history. On one balcony he saw an old man in a black papakha—a tall fur hat. The old man was warming himself in the sun, his shoulders wrapped in a burka (a long felt cloak). Seeing the stranger, the old man nodded to him with dignity. Shurik bowed politely in return, remembering the rule of respect for elders.

In the center of the aul there was a tiny square—a widening of the street near a ram-shaped fountain. Clean water was streaming from the stone head of the ram. A few women were filling their pitchers and chatting with each other. Seeing Shurik, they immediately smiled. One of the women in a bright headscarf asked the children:

“Is this the guest from the capital?”

“Yes, it’s him!” the kids answered in chorus.

The woman set down her pitcher and walked up to Shurik warmly.

“Welcome, guest! We’ve been expecting you. My name is Fatima. I’m the niece of Jabra’il, with whom you’ll be staying.”

“Hello,” Shurik replied with relief. “I’m very glad to meet you! Thank you for agreeing to host me.”

Fatima turned out to be young—a little older than Shurik himself—with radiant brown eyes. She wore a long blue dress embroidered with patterns, and over her shoulders draped a light white shawl. Her smile was open and kind.

“We are always happy to welcome a guest,” she said. “In our place, people say: ‘A guest in the house is a messenger from God.’ We consider it an honor to feed and shelter a traveler.”

Shurik immediately felt himself a welcome visitor. Fatima pointed out to him a small saklia—a traditional stone house—where her uncle Jabra’il lived. The house looked old: thick stone walls kept the interior cool, and the flat roof was covered with turf. In the yard of the house grew a walnut tree that provided shade.

Before entering the house, Shurik instinctively stopped at the threshold and wiped the dust from his boots. He knew that upon entering, one should remove one’s shoes. Fatima held the door for him, inviting him inside. Shurik noticed that the doorstep was carefully swept and even decorated with patterns. Fatima gently warned him:

“Careful, don’t step directly on the threshold. We have a belief: you mustn’t step on the threshold; you step over it. It’s the boundary of the home, and it shouldn’t be trampled.”

Shurik nodded and stepped over the threshold, committing another piece of local wisdom to memory.

Inside, the house was cool and cozy. The room they led him into served as the living room. At the far wall, a hearth was burning—a small fire in a niche. Its smoke rose upward and escaped through an opening in the roof instead of a chimney. Thin twigs crackled in the hearth, and a kettle hung over the fire. By the hearth sat the master of the house himself—Jabra’il, Fatima’s uncle. He was an elderly man with a gray mustache, wearing a simple homespun shirt. Next to him, a little boy was playing on a rug—likely Fatima’s son or nephew.

“Peace to your home,” Shurik greeted politely in the Caucasian manner.

“And peace to you, and welcome!” Jabra’il replied, rising. He shook the guest’s hand with both of his, in a friendly way. “How was your journey, dear guest? The road in the mountains is not short.”

“Thank you, everything was fine,” Shurik answered. “I rode a passing bus from the city, and walked the last few kilometers on foot. But now I can admire your wonderful aul!”

Jabra’il smiled and seated the guest in the place of honor—by the wall where soft embroidered cushions lay. Meanwhile Fatima hurried to the hearth: she removed the kettle from the fire and began pouring tea into small piyalas (tea bowls).

The little boy who had been playing by the hearth crawled closer to the guest with interest. This was Jabra’il’s son, five-year-old Ali. With a serious air, he set a low serving table in front of Shurik, and Fatima was already placing on it a bowl of fragrant tea. Shurik noticed a pinch of salt and a piece of butter had been added to the tea—highlanders drink tea this way to warm up and gain strength. Next to it appeared a bowl of honey—dark amber and viscous. The hosts invited the guest to help himself.

“Thank you very much,” Shurik said, taking a sip of tea. The drink was unusual—slightly salty and buttery, but surprisingly invigorating. It went perfectly with the sweet mountain honey scented with herbs. “What delicious honey! So thick.”

Jabra’il smiled, stroking his beard. “This is thyme honey. Our bees gather it from thyme flowers high in the mountains. It’s both tasty and healing—it helps with colds better than any medicine.”

Shurik looked around the room. The walls were adorned with antique daggers in carved sheaths and a round shield. In the corner stood a large wooden chest, banded with iron and decorated with patterns. On the lid of the chest were carved images of the sun and finely interwoven lines.

Fatima noticed his interested gaze and said with a smile, “This chest is my dowry. It holds fabrics, a dress, jewelry—everything my parents and relatives gave me for my wedding day. We have a custom: to make carved chests for the bride so she can carry a piece of her parental home to her new house. The ornaments on the chest are talismans, to ensure the family will be strong and happy.”

Shurik nodded, impressed by how reverently traditions and symbols are treated here. Everywhere he noticed evidence of the ancient way of life: an old forged chain hung above the hearth—the hearth chain on which a cooking pot is hung. Following the guest’s gaze, Jabra’il explained: “This chain is the heart of the home. It’s passed from father to son. The hearth is a symbol of the family. There’s even a custom: when a young couple builds a new house, they take fire from the old parental hearth and carry it to the new place, so that the connection between generations is not broken.”

Soon neighbors began to come by the house—to see how the guest was settling in. Each brought something tasty with them: one brought a bowl of walnut jam (here it’s customary to greet guests with such jam), another brought khychin flatbreads with cheese and potatoes, a specialty of the Balkar people. In a short time, the low table in front of Shurik was filled with treats. Here was steaming shashlik (grilled meat on a skewer), aromatic and smoky. There was a plate of Ossetian pies—round, golden, stuffed with cheese and herbs. Three such pies were stacked on top of each other.

“Ossetian pies—always three,” Jabra’il explained. “They symbolize God, the Sun, and the Earth. It’s our custom: on big celebrations we serve three pies; it’s our tribute to the Almighty and nature.”

Shurik carefully broke off a piece of pie. The dough was soft, the cheese stretched in appetizing strings, and the aroma of herbs filled the air. The guest ate with pleasure. He was also poured a small cup of ayran—a cool, sour dairy drink that perfectly quenches thirst.

“Eat, dear, please,” the hostesses repeated, pushing more dishes toward him. “Don’t be shy, you’re fresh off the road.”

Though Shurik was already full, he could not refuse—such is the tradition of hospitality. He remembered: to refuse a host is to offend them. So he tried a bit of each dish, praised the taste, and thanked them. His heart filled with warmth from such care.

Over conversation, Shurik told them about himself: how he had dreamed of seeing the mountains since childhood, how he had read books about Caucasian customs. He mentioned that his suitcase contained an entire notebook for riddles and legends that he hoped to hear here.

“We’ll find you storytellers,” Jabra’il winked. “In the evenings by the fire, we love to tell tales and legends. The elders know so many stories!”

“And our highland songs are sung too,” added one of the neighbors, pouring tea into the piyalas. “We’ll invite our ashug—a folk singer—he’ll play the saz and sing ancient ballads for you.”

Shurik nodded happily. He had already begun to take out a notebook to write down everything he saw and heard, but the host raised his hand.

“No taking notes now! First enjoy the refreshments. Work can wait. You are our guest—rest after your journey.”

Everyone nodded approvingly. For the mountaineers, a guest comes first, and caring for them is above all else.

Shurik blushed and set aside his notebook. At that moment little Ali, the host’s son, accidentally bumped an elbow against the salt shaker on the table. The salt shaker tipped over, and a small pile of salt spilled onto the tablecloth. Everyone fell silent for a moment. Ali looked fearfully at his father. But Jabra’il did not get angry. He only said seriously:

“Spilling salt brings a quarrel. No matter, we’ll fix it now.”

Immediately Fatima quickly gathered the spilled salt with her hand and threw it over her left shoulder. Then she spat three times over her shoulder (of course, only symbolically). Everyone laughed, and the tension melted away.

“There we go, the trouble is averted!” said a neighbor. “There will be no quarrel, only peace.”

Shurik noted to himself: even the small omens and customs are respected here, turning them into a cheerful ritual.

When the tea was finished and the dishes were empty, Jabra’il announced solemnly, “Now, friends, allow me to offer a toast to our guest.”

Everyone fell silent and raised their cups—some with tea, some with homemade wine diluted with juice. The host stood up:

“Dear Shurik!” he began loudly. “We are glad to see you under our roof. May you feel better here in our home than in your own. To your good endeavor—studying our traditions. May your head be strong and your memory clear, so you can preserve everything you learn. Welcome to our family!”

“To the guest!” the neighbors and relatives proclaimed in unison.

Everyone drank—some tea, some a sip of compote. Shurik also sipped his drink, moved by the warm words. He stood and bowed slightly.

“Thank you all so very much. I am happy to be here and I promise to treat all your customs with respect.”

Outside the window the sun had risen higher, and sounds drifted in: somewhere nearby a garmon (accordion) was playing—perhaps a musician starting a melody for a good day. Children ran laughing along the path. And in the distance, on the green slopes, appeared a flock of sheep driven by two shepherds in burkas, with shepherd’s staffs in hand.

Shurik watched the life of this mountain aul and felt that he had entered a special world where every little thing has significance, where people live by the laws of honor and kindness. He did not know what adventures awaited him ahead, but he was full of determination to see everything with his own eyes and, if fortune favored, even take part.

Thus began his first morning in the mountains. Shurik did not yet know that ahead of him lay mysteries and trials in which he would need his knowledge, his powers of observation, and his deductive mind—like Sherlock Holmes, only here among the majestic peaks of the Caucasus.

Chapter 2. First Encounters

A day passed, and Shurik had time to get a bit settled in the aul. Together with Ali and other children, he went to the river to watch how the old-timers catch trout in the cold rapids. They showed him the terraced fields on the slopes, where corn and barley ripen on narrow strips of land. He saw how women baked fresh lavash in a clay oven—a tandoor—right in the yard. They deftly took out the hot flatbreads using a special long stick, and the aroma of bread spread throughout the area.

In the evening the whole aul gathered in the square—the little flat courtyard in front of Jabra’il’s house. The neighbors organized a small celebration in honor of the visiting guest. The tamada—the toastmaster of the feast—turned out to be a mustachioed neighbor named Ruslan. He announced loudly:

“Today we welcome a dear guest from afar! Let’s show him our dances and songs, so he takes away a piece of our soul with him.”

In the square they lit a small bonfire and set up long wooden benches around it. The women brought treats: roasted lamb, vegetables, herbs, fruits—cherry plums and peaches, fresh cheese and, of course, flatbreads. The children milled around in anticipation of fun.

With the first sounds of the garmon (accordion), it became clear that Shurik had stumbled upon a true dance evening. There were claps in rhythm, the melody sped up—and suddenly a young man dashed into the center of the circle. He swung his arms, crouching low, then straightened sharply—and began striking a rapid staccato rhythm with his feet. It was the Lezginka—the famous Caucasian dance. The young man moved like a proud eagle: swift, precise, with fire in his eyes. After him, a girl in a long dress with a narrow belt gracefully stepped into the circle. She glided like a swan—smoothly, softly, her gaze modestly downcast. The young man circled around, tapping his heels on the ground, now approaching her, now springing back without touching—since in this dance the young man must show respect and admiration for the girl without ever laying a hand on her.

Shurik watched, entranced. He had taken out his camera to record the dance, but then decided to just enjoy the moment with his own eyes. When the Lezginka ended, everyone applauded. The children squealed with delight, begging for more.

“There will be more!” laughed Ruslan the tamada. “But first—a song!”

A short, slender old man with silver at his temples came to the center. In his hands was a stringed instrument—a saz. He sat on a stool and plucked the strings, tuning them. Silence fell. Shurik realized that this man was an ashug, a folk singer-storyteller.

The first sounds of the melody rang out—sad and beautiful. The old man began to sing in a low voice, a song in an unfamiliar language. Shurik didn’t understand the words, but he felt each note with his heart. It seemed as if the very soul of the mountains was singing of love and separation, of the bravery of jigits (mountain warriors) and the beauty of maidens. The wind caught these sounds and carried them to the peaks, and the stars appearing in the sky twinkled in time.

When the song ended, many stood with moist eyes—so deeply it had touched their souls. Shurik quietly asked Fatima, “What was that song about? I didn’t understand anything, but I feel as if I lived a whole life in those minutes.”

Fatima smiled. “You felt it correctly. The song is about a brave young man who, for the sake of saving his bride, rushed into battle against enemies. About how his love gave him the strength to overcome all obstacles. They say that legend took place somewhere here in our area, many years ago.”

Shurik sighed. How that resonated with his own dreams—to witness a true story of love and courage in the mountains. He thought that such songs are the heart of the people, their unspoken code of honor.

After the song came games. The youth organized playful contests: tug-of-war, sack races. Everyone laughed and cheered each other on. They invited Shurik to participate as well, but he modestly declined, preferring to watch.

Then the tamada raised his hand again: it was time for another toast. A large carved goblet filled with homemade grape juice was handed to him. The tamada stood and proclaimed:

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «Литрес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на Литрес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.