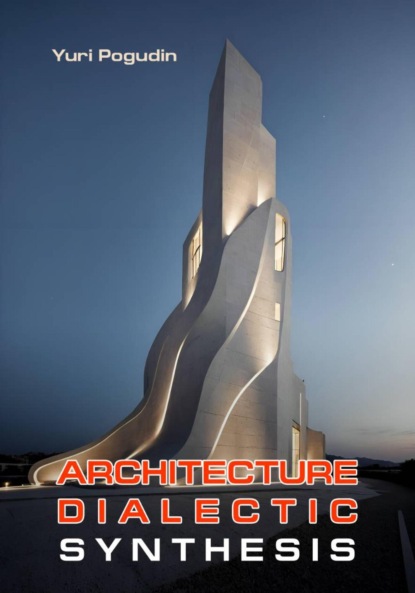

Architecture. Dialectic. Synthesis

- -

- 100%

- +

Another common attempt to determine the architectural form is to explain it in terms of climatic conditions. The simplest definition of architecture says that it is a set of structures designed to protect humans from atmospheric phenomena. The need to take shelter in bad weather sometimes explains the very origin of architecture. Without denying the essential role of weather and climatic conditions in form generation, it should nevertheless be emphasized that it is not decisive either in the origin or in the development of architecture. Architecture would undoubtedly have arisen in such a hypothetical case if the climate and weather were favorable everywhere. After all, there are many buildings and structures (for example, religious ones), the appearance of which is in no way due to these factors. There is a well-known idea that if the Greeks had built a temple on Olympus, where it never rained, it would still have had a pediment. Rain causes only the sloping nature of the roof, but there are many specific options for sloping roofs. This means that when completing the temple with a roof with two symmetrical slopes, the Greek architect was guided not by meteorological knowledge, but by the principles of his worldview. The form-generating action of the architect becomes an act of expressing a worldview that is not constrained by either climatic conditions or economic opportunities.

Summarizing, it should be said that architecture is the material correlate of philosophy. Architecture and philosophy are correlative, like matter and idea. Just as philosophy performs an integrating function in the worldview sphere, architecture performs an integrating function in the sphere of material and bodily life. Just as philosophy synthesizes the knowledge of all sciences into one whole, architecture synthesizes different aspects of human bodily life in one indecomposable synthesis of items of determining positions of material works.

Let us conclude our discussion with a general definition of architecture: it is the construction, aesthetic and technical designing of the material structure of the natural space as a housing and economic environment.

The General Architectural Ennead

Function – Aesthetics

The understanding of architecture is usually based on the Vitruvian triad of strength – usefulness – beauty or, in other words, design – function – aesthetics (artistic imagery, composition). Accordingly, constructive, functional and aesthetic aspects are identified in architecture in general and in individual buildings.

The most acute opposition in this triad is characteristic of the categories of function and aesthetics, which has found historical expression in the antithesis of classical ("old") and modern ("new", modernist) architecture. The latter is characterized as functionally conditioned, and the first one as saturated with various kinds of non-functional decorativeness. The term "minimalism" appears at one pole, and the concept of "architectural excesses" at the other.

The third part of the Vitruvian triad – strength or construction – eventually ceases to be a category defining the identity of architectural activity. Universal masters, engineers and artists in one person, such as Pier Luigi Nervi and Santiago Calatrava, continue to appear in architecture. But this does not change the general vector towards the gradual "dematerialization" of architecture. It is noteworthy that A. V. Ikonnikov named one of his books "Function, Form, Image in Architecture," thus leaving the topic of materials and structures out of the main discourse.

The understanding of architecture is based on the pair of "function-aesthetics". The structural system plays the role of a means to achieve functional and aesthetic goals.

Let's start our search for the dialectical foundations of architecture with the opposition "function-aesthetics". Opposites arise from the initial identity, and, having passed through the stage of confrontation, they unite in the separable integrity of synthesis. What are the opposite features of function and aesthetics?

A function in the most general sense is an activity. A function always implies that or who is functioning, acting. The function itself is used only in an abstract mathematical field. For architecture, functionality, including ergonomics, is primarily related to human physicality. It is precisely as a function of the body that the function is opposed to decor, decorations, etc., which do not give anything to direct physical comfort. But if we do not reduce the fullness of human nature to body alone, then we should talk not only about the function of the body, but also about the function of the soul and spirit, and, generalizing, about the function of man as a spiritual, mental and physical whole. If we understand the function in such a way, it becomes possible to overcome the antithesis of function and aesthetics. Aesthetics in this regard becomes a psychological and spiritual function18. The ideal side of a person is formed by the antithesis of mind and heart. According to the structure of a person, one can distinguish between the function of the mind, the function of the heart, the function of the will, etc. The function of the mind in its most general form is philosophy, since it is philosophy that is engaged in integrating all scientific, religious and other knowledge into one integral worldview. From this point of view, when an architect seeks to create a "theology in stone" in a temple, his actions are also functional, and temple architecture is spiritually functional. The functionalism of the twentieth century is the result of reducing architecture to purely materialistic understanding.

Aesthetics, which nourishes the human mind and heart, is perceived primarily visually. The tented roofs of ancient Russian churches serve as an illustration to the theological idea (striving for God) and a spatial landmark at the same time. This is just one example against a narrow understanding of the function. It is well-known that the space below the tented roof of the temples was completely unused and was isolated by the ceiling from the main part of the temple, where worship was held, as otherwise additional heating costs would have been required.

A function is the "what" of architecture, it is its content, what architecture expresses and formulates. Architecture is the architecture of the human function as a whole. Man in his functioning is the content of architecture and architectural creativity. Architecture, therefore, is the otherness not only of the body of a person, but of his entire nature, including his mind and worldview. Just as man himself is a synthesis of ideal and material principles, so architecture, which continues his being in nature, becomes a synthesis of the dwelling of the body and the dwelling of consciousness (ideology, mythology). And this is aesthetics that forms the second – ideal – plan, layer of architecture. Aesthetics is the architectural "how" of mythological eidos. Function and aesthetics are related as "what" and "how", or, according to the antithesis common to all art, as content and form.

Considering aesthetics from the point of view of function suggests the opposite. One of the examples of understanding function through aesthetics is given by the aphorism of F. Johnson: "The beauty lies in the way you move in space.19" Johnson obviously meant the movement of the body, but one can expand the concept of "movement in space" to the movement of the soul's feelings in the space of art, the movement of the mind in the space of philosophy.

Thus, aesthetics and function are dialectically interrelated. But this is not enough for dialectics, and having separately considered any categorical opposition, it seeks to synthesize it into a new integral category. For the antithesis of function-aesthetics, it is the architectural form itself that plays the part of such a synthesis.

It should be noted that a completely natural separation of function (in the sense of body function) and pure aesthetics is possible in special types of architectural creativity. There is a whole complex of structures that have no utilitarian purpose – such as monuments, triumphal arches, etc. They are completely dominated by the aesthetic principle. At the same time, there are whole types of architecture, such as industrial and fortifications, where function plays a crucial part.

Let's summarize the identified triad:

1) Functional and aesthetic original identity

2) The antithesis of function and aesthetics

3) Functional and aesthetic synthesis: architectural form

This triad reveals the dialectic of architectural eidos. Like any eidos, it strives to embody and become tangibly manifest, which transfers us into the sphere of architectural meon20.

Structure

The architectural eidos was based on the antithesis of function and aesthetics. Let us now find a meonal category embodying architectural eidos as an immobile substance.

The main quality of a substance is immutability. Immutability, considered from the point of view of pure change and pure temporal fluidity, is eternity. What is immutability, understood as eternity, in the sphere of architecture, which is meonal from the point of view of the first architectural and semantic triad? It can only be a very long stability in time, that is, durability. Durability is a correlate of immutability in the architectural field. If the substance is characterized by immutability, then the structure has (or should have) durability in architecture. Thus, structure is the substance presented architecturally.

What is a structure in itself?

In its most generalized form, a structure can be defined as a system of conjugations of material elements of an architectural form, realizing it as a material, substantial facticity. It is a way of the form existence in the world of dense matter.

Let us now define the structure through correlations with other areas.

Since the category of architecture is based on the category of the human body, let us find the bodily correlate of the structure. It's a skeleton. If the structure is the skeleton of a building, then the function is the totality of its systems and internal organs, and aesthetics is the living flesh of the image. As F. L. Wright wittily pointed out, Wright, "rattling bones is not architecture21." Cultivating a structure as an aesthetic value in itself is similar to the desire to express in speech not its meaning, but the grammatical rules of its construction.

From the general definition of the structure, let's move on to its detailing. Strength, stability, and rigidity are the main properties of a structure.

Strength is a function of a structure, consisting in its ability to maintain itself under various loads. This is the self-identity of the structure in relation to the moment when it began to experience the pressure of the load (or some other impact). If in the case of strength we are talking about the fundamental existence of the structure – its ability not to collapse under exposures and loads, then in the case of stability we mean the identity or constancy (equilibrium) of the spatial position of the structure under the same exposures and loads. Rigidity is characterized by the moment of immutability (or nuanced immutability) of the structure itself, without taking into account the general spatial position. Thus, it is possible to arrange the three known qualities of the structure into a sequential triad, where the same quality – constancy (otherwise identity, substance) in relation to loads and exposures – gives each time a new category depending on the type of semantic correlation:

1) The structure itself, as an actual reality: rigidity

2) The existence of the structure: strength

3) Spatial position of the structure: stability

Thus, a structure is the constancy of an architectural form in the world of actual substance, the realization of its substantial self-identity. A structure is the "how" of the material existence of the "what" of an architectural form.

Let's note that when understanding the form-structure relationship through the internal-external antithesis, these opposites flow into each other. In purely semantic terms, the form is, of course, "internal", that is, what is realized, and the structure is "external", what realizes. But in terms of material facticity, it turns out the opposite way: for the bodily sense of touch, the form is something external, the living flesh of the building, and the structure is its inner skeleton. Thus, during the transition from the ideal plan to the material one, the form becomes "external" from the "internal", and the structure, on the contrary, becomes "internal" from the "external".

Further development of the concept of structure involves the consideration of types of structures and is not included in the objectives of this work.

Layout – Tectonics

The structure is the first principle of the architectural meon. The second principle in architectural eidos is the antithesis of function and aesthetics. Now it is necessary to present a meonal modification of these categories from the point of view of the structure.

What is a function given in the architectural meon, in space and considered from the structural point of view? A function is a movement, a multi-component process that takes place in a building, to a building, through a building, and out of a building. Structural modification of a function means that it is taken as a system of spaces that organize the process of human activity. The system of spaces that defines the places of their isolation and overlapping is a layout. The layout is the formation of a function.

The layout should provide not only one particular function, but also be ready to flexibly respond to various life changes. The functional flexibility of the layout is one of the qualities that make the building vital and durable. The functional system of constructivism of the 1920s is characterized by invariance22, and I. Leonidov, contrary to the general trend of this movement, "sought to universalize the type of building – one spatial composition for a number of functions.23" Later, this trend was crystallized in the Seagram Building by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Among foreign architects, the flexibility of the layout also characterizes the works of K. Tange.

Further, let's modify the aesthetics category in a similar way. Aesthetics, given as a structure, is tectonics. Tectonics is not only an aesthetic interpretation of a structure, but also a structural expression of aesthetics. The demonstration of the structure's work has ideological and symbolic significance. Tectonics is the framework of mythological eidos given in the structure.

Let us briefly consider the types of tectonics. The main types of tectonics are the tectonics of material and the tectonics of space, according to the understanding of architectural form as a material and spatial synthesis. The tectonics of the material is antithetically divided into heaviness expression tectonics and heaviness overcoming tectonics.

When form and structure are identical (direct demonstration of the structure), it is called constructive tectonics. If the form and structure do not match (for example, the form envelops the structure without giving an idea of its work), it is called atectonics (for example, the Baroque style). When synthesizing form and structure, we speak about artistic tectonics: "a plastic form reflects the fundamental features of the structure.24"

Thus, the second architectural and meonal principle is formed by the antithesis of layout/tectonics. Layout is the tectonics of functional space, and tectonics is the structure of aesthetic space expressing myth.

The next step is a synthesis of tectonics and layout, correlated with the architectural form of the sphere of eidos. It is a building given as a fact or the fact of a building, that is, a building taken solely from the point of view of materiality, as a material that has become25.

Summarizing, the architectural meon looks like this:

1) Structure.

2) Layout – Tectonics.

3) The fact of the building.

The next logical area after the sphere of eidos and the sphere of meon is the sphere of synthesis of both, completing the overall architectural ennead. The synthetic domain, like others, contains its own identity, its own difference and its own synthesis, but the data are already as holistic as possible, as a synthesis of idea and matter. It all starts, as before, with the original identity of opposites, which we will call the architectural essence. The architectural essence is polarized into internal and external part, which are then synthesized in their unity. Let's move on to the specific dialectic of the external and internal in architecture.

Interior – Exterior

A building, as internal to itself and as external to itself, is, respectively, an interior and an exterior. The interior is the building in its internal expression, the interior of the building. The existence of the interior distinguishes an architectural form from sculptural and other forms. A sculptural form is a purely exterior form, it is external to itself. The interior contains the specifics of architecture as a container. The interior is the building's inward orientation, into itself as an integrity distinct from the environment. The exterior is, on the contrary, the building's exit outside, into the external world, its manifestation to the space of the surrounding world.

This only captures the antithesis of the interior and exterior as the opposition of the building to itself. Dialectics then examines categories from the point of view of their otherness, and establishes the transition of opposites into each other. Otherness to the building is a human subject. The interior is a form encompassing this subject. Consequently, the subject turns out to be an internal content in relation to the interior, and the interior in its relation to the subject is an external thing. The exterior category also undergoes a similar transition to its opposite when correlated with the otherness. The exterior in relation to the subject presupposes the possibility that the perception of the subject embraces it, if not simultaneously, then sequentially, with the in a circular, ambient motion. This means that the exterior is the inner content in the encompassing perception of the subject.

So, during the transition from the building-for-oneself to the building-for-the other and back, the external flows into the internal (and vice versa) within the framework of the interior-exterior antithesis.

There is another type of overflow of these categories – when moving from one to many in the category of architectural objects. This refers to a situation where many buildings, each of which is individually given externally, organize an interior urban space, provided that their layout is relatively closed. Such an example is a square. The same can be established regarding the direction from the interior to the exterior. If there is a number of rooms connected in a closed arc-shaped enfilade flow, then there is created the possibility of encompassing the perception of a part of the interior space, and this introduces an exterior moment in perception.

The next task of dialectics is to synthesize these categories. The synthesis of interior and exterior is the building considered as a whole. Leaving behind the discrete consideration of the building from the inside and from the outside and absorbing its integrity in a single semantic act, we are already returning to the original identity of the interior and exterior, but now with the preservation of the moment of their distinction. This synthesis, as a self-identical difference, is the building as a unity of container and shell, an integral architectural unity.

Let's combine the summary of the "interior-exterior" section with the previous results into a single categorical structure:

Architectural Ennead26

Architectural eidos:

a) Functional and aesthetic original identity

b) Function – Aesthetics

c) Architectural form

Architectural meon:

a) Structure

b) Layout – Tectonics

c) The fact of the building

Architectural integrity:

a) Architectural essence

b) Interior – Exterior

c) The building as a unity of container and shell

The proposed ennead summarizes the most basic architectural categories. Further movement along the planned path leads us to more specific architectural concepts such as scale, wall, window, etc. We will consider them not only from an abstract logical point of view, but also from a specific mythological one.

Scale Category

The first chapter dealt with the embodiment of human consciousness in architectural matter. This process is accompanied by the reverse process: once erected, the building begins to live in the physical space and in the space of human perception. The architectural object is embodied (in other words, it affects) In human consciousness, primarily in the most general category – size or magnitude. In human perception, this category is modified into a scale system. The size of the building either dominates consciousness (mega-scale), or is relatively small (micro-scale), or, finally, is commensurate.

Next, it is necessary to give a clarifying modification of the scale category in connection with the human body. A person perceives the dimensions of a building not only as an object "in itself", but in relation to the size of his body. According to the previous division, the buiding can be commensurate with the human body, and therefore psychologically comfortable. If the building is disproportionate, they speak of the "indefiniteness of the physical dimensions of the structure.27" This method of realizing size in perception was used by ancient Egyptian architects, creating colossal undifferentiated arrays of pyramids. The masters of the Western European Middle Ages, on the contrary, introduced many divisions into the flying vastness of space. It is no coincidence that O. Mandelstam in his poem connected Gothic with "Egyptian power": Egyptian structures are the power of the material expressing heaviness, and Gothic buildings are the power of space, overcoming this heaviness.

Summarizing the above in relation to the architect's work, we can say that the essence of the scale system is that by adjusting the degree of fragmentation of the volume, it is possible to control manifestations of its size in human perception, that is, to increase, decrease or reveal equivalently to the real physical size. The architect chooses one way or another to synthesize the size of a building and its perception by a person, depending on the nature of the mythological eidos he embodies. Here are some more examples from classics and modern times. We find many variants of "direct correspondence of proportional scale characteristics of architecture to the size of the human body in the ancient experience… <…> However, the ancient Greeks, and after them the Romans, creating spaces for human habitation and activity adapted to man and commensurate with him, never forgot that the house of god – a temple – must have different qualities and a different scale than a human dwelling, so that a person entering a temple feels that he is not going to his own house, but to the house of god.28"

In modern architectural practice, there are examples of other applications of the scale system, related not to mythological attitudes, but to the development of architectural science as such. Thus, one of the main provisions of Soviet rationalism, put forward by N. Ladovsky, was "saving mental energy in the perception of spatial and functional properties of a structure.29" According to this thesis, the architect should make every effort to ensure that the geometric characteristics of the building are read as adequately as possible. The opposite approach is observed, for example, in the works of the Finnish architect Reima Pietilä, who does not open the entire structure and suddenly amazes those who enter with the vastness of the interior spaces.