Architecture. Dialectic. Synthesis

- -

- 100%

- +

Let's also note that the relativity of scale system consists in its dependence on the age of the perceiving person, on his height, as well as on the specific features of the process of visual perception of forms and spaces30.

The Dialectic of Function

The basic functional typology of buildings and premises is derived by us on the basis of the triune hierarchical structure of human nature. In accordance with the triad of spirit, soul and body, we will distinguish:

1)

the architecture of the spirit

(sacred, temple architecture)

2)

architecture of the soul

(museums, theaters, universities, libraries, cultural and community centers, etc.)

3)

the architecture of the body

(restaurants, hotels, industrial buildings and structures, etc.)

Further, the same triple division can be carried out in the interior system inside a residential building. After all, a residential building is a type of building that accommodates almost all human functions. The design and realization of bodily needs include rooms such as a kitchen, dining room, bedroom, bathroom, etc. Hierarchically higher are rooms such as the living room, study, workshop, related to the mental organs and their functions (communication, cognition, creativity, etc.). Even higher is the area of the spirit, the room where a person realizes his religious faith, for example, the room where he prays. Inside a palace or university, it is a temple that is a part of it. Inside a separate room in a Russian hut, there was traditionally a "red corner" with icons. It was in this corner that K. Malevich hung his symbolic black square, which thereby proclaimed the formation of a black hole in the human soul, expelling God from his life.

Thus, the first functional antithesis arises – sacred, consecrated and ordinary premises both in the general structure of the building and as a special type of buildings. Juri Lotman writes about this as follows: "The house (residential) and the temple oppose each other in a certain respect as profane to sacred. Their juxtaposition is obvious from the point of view of cultural function and does not require further reasoning. It is more important to note the common feature: the semiotic function of each of them is gradual and increases as it approaches the place of its highest manifestation (the semiotic center). Thus, sanctity increases as one moves from the entrance to the altar. Accordingly, the persons admitted to a particular space and the actions performed there are positioned gradually. The same gradation is characteristic of residential premises. Names such as "red" and "black corner" in a peasant hut or "black staircase" in an apartment building of the 18th and 19th centuries clearly indicate this. The function of a dwelling is not sanctity, but security, although these two functions can overlap: the temple becomes a refuge, a place where protection is sought, and a "holy space" is devoted in the house (hearth, red corner, the role of the threshold, walls protecting from dark forces etc.)31.

We have identified the antithesis of ideal (spiritual and mental) and material (bodily) functions. Is their synthesis possible?

If the concept of a material function includes the function of protection from the enemy (fortification), then one of the clearest examples of synthesis is the Athenian Acropolis. The acropolis, a fortified part of an ancient Greek city, by definition, performs a twofold function – it contains temples of the deities under whose protection the city is located, and serves as a shelter for the townspeople during attacks32.

Another example of synthesis is a medieval monastery. This is a place of residence for monks, a defensive fortress, and a crossroads of trade routes, the goal of pilgrims, not to mention the self-evident main function of promoting the salvation of the soul.

According to the functions of communication (socially given identity), privacy (socially given difference) and their complex conjugation, one distinguishes between communication spaces (living room, kitchen, etc.), privacy spaces (study, bedroom, etc.), and mixed types of spaces. It should be noted that the oppositions of ideal – material functions and communication—privacy functions are not correlative and therefore overlap each other in the system of living spaces. Thus, the study and the bedroom, which are opposite in the first of these antitheses, are identical in the second function (privacy).

The next, equally important antithesis of the functional sphere is the opposite of living space, recreation space and work space. In megacities, this antithesis causes discomfort to many people from the spatial separation of "sleeping areas" and institutions, enterprises, offices clustered in the central part of the city.

The synthesis of dwelling and work functions at the level of individual houses is interesting. Here again, we recall the tradition that lived in the Middle Ages as well of placing living quarters and work premises (on the ground floor) in the same building. There are examples of such a synthesis in modern architecture. Thus, a complex of villas has been built in Berlin, each of which "performs, in addition to the residential function, the tasks of an infrastructure element. This is achieved by the fact that each villa is inhabited by an entrepreneur whose company is engaged in public service and it is located in the same house <…>. Such an unusual for modern urban planning method of performing "social, cultural and residential function" essentially revives the traditions that were forgotten today, when a merchant lived above his shop… Combining dwelling and a place of work in one building acts on the one hand as an effective method of saving urban land, and on the other hand allows you to erect significant construction volumes that carry a representative essence, important for the owner and ensuring the urban significance of the building.33"

There are two more important antitheses inside a separate building:

1) The main premises are service, connecting premises (communications – elevators, stairs, corridors, etc.). The synthesis between them takes place at the aesthetic level, when communications are not hidden in the thickness of the building, but are brought out, participating in the creation of the artistic image of the building and giving the opportunity to feel its inner life from the outside34.

The project of the new city by architect A. Sant’Elia in 1914, brought this principle to its ultimate state: the basis of spatial composition is determined by the communication system. Examples of a "moderate" synthesis are the theater building in Rostov-on-Don (architects: V. Shchuko and V. Gelfreich, 1930-1936), the Gosprom (Derzhprom) building in Kharkiv (S. Serafimov, M. Felger, S. Kravets, 1925-1928).

2) Servant vs. served spaces. This antithesis was of particular importance in the work of L. Kahn. The American architect developed the thesis about the separation of these types of rooms. "Working on a small facility, a swimming pool, led me to the theory that the servant spaces and the servant ones should be separated. This distinction has become the basis of all my plans.35"

The opposite approach to the solution of the internal functional space is presented in the concept of another famous American architect, F. L. Wright. He put forward the thesis of "the unity of the internal space.36"

From a dialectical point of view, an approach is possible that does not place a separate emphasis on either the unity or the separateness of the building spaces, but follows the principle of single separable integrity. In addition to pure dialectics, such a teaching has deep foundations in the modern understanding of the physical structure of space. Space is created by light, which is characterized by wave-particle "wave-particle "duality" (one can say "synthetism"). Depending on the specific circumstances, light behaves either as a particle or as a wave. The physical world turns out to be a school of dialectics. After all, a particle is nothing but a materially given identity (as a point is the identity of the beginning and the end), while a wave is a difference in the quality of extension (as a line is the difference of the beginning and the end). Thus, physical space is a single separable whole. This is an additional basis for formulating a similar doctrine in relation to the functional space of architecture.

Let's list the main antitheses of the architectural and functional environment:

1) sacred – ordinary;

2) communication spaces – privacy spaces;

3) working and residential spaces;

4) connected – connecting rooms (communications).

5) served (main) – servant (subordinate).

These antitheses reveal the dialectic of function in general terms. So far, we have considered architecture primarily as one or another organization of space. But space is inseparable from time and from history. Taken from the point of view of temporal formation, architecture reveals to us the whole complexity of the historical relationship between the old and the new, the past and the future. The second part of the work is devoted to the historical formation of the architectural form.

The Antithesis of Historical Space and Architectural Form

The antithesis of the new and the old, from the point of view of architectural history, is the antithesis of traditional and innovative architecture, classical and modern, avant-garde one. Classical architecture itself contains this juxtaposition of antiquity and the Middle Ages. The frame system of the Gothic cathedral is something radically new in comparison with the rack-and-beam system of the Greeks. "Classics" and "avant-garde" permeate the entire history of architecture.

In architectural creativity, this antithesis in its untamed form has given rise to two opposing approaches to design. In Soviet architecture, I. Zholtovsky was a prominent advocate of the growth of new forms based entirely on the experience of past architecture. Such architects as K. Melnikov, I. Leonidov stood for principal innovation. So, "Leonidov had a strongly negative attitude towards architects, for whom the creative process is the use and processing of some forms and details that have already been created by other architects. He did not even recognize them as genuine architects, because, in his opinion, they do not understand the meaning of the architect's work, they make architecture purely externally, and not from the inside, which is not real creativity. They take something ready-made and put things together from it. Leonidov considered I. Zholtovsky to be an architect of this type, therefore, he was highly critical of his talent and creative style. Leonidov was convinced that beauty cannot be composed of elements of ready-made beauty, but must be created anew. In this, he really radically disagreed with the creative concept of Zholtovsky, who saw in the legacy (that is, in the works created by others) an inexhaustible source of compositional ideas, forms and details.37"

Already in our time, Frank Gehry spoke vividly about the role of the past: "You can learn from the past, but not continue to be in the past. I can't look my children in the eye if I say I don't have any more ideas and have to copy the past. It's like giving up and saying they don't have a future anymore.38"

In order to keep in touch with the past and at the same time make a move into the future, in order to ensure the historical comprehensiveness and full value of the architectural form, it is necessary to combine both approaches in design. An example of such a synthesis is the work of St. Petersburg architect Igor Yavein. "A thoroughly erudite man, Yavein knew well and studied the history of world architecture throughout his life <…>. But when he started designing, he didn't use special literature: he kind of started everything from scratch, without any prototypes or sources.39"

The history of architecture knows attempts to synthesize the "old" and the "new" at the level of entire trends. One of them is "a unique and little-studied movement of the 1920s and 1930s – Art Deco. It was a phenomenon of architecture of the "integrating type". Based on the innovations of the pioneers of new architecture, Art Deco did not break with history." But "it was, to a certain extent, a continuation of eclecticism," 40according to Yu. I. Kurbatov, and therefore did not last long. Any eclectic combination is short-lived due to the external nature of the conjugation of different forms. Dialectics directs us towards combining the very principles of classical and avant-garde form creation into new synthetic principles.

It should be noted that "an analysis of the means and techniques of artistic expression of the new architecture shows that much of them not only has a continuity with the past, but also does not go beyond the established stereotypes.41" This suggests that despite the visual gap between the old and the new architectures, they have a lot in common at deeper levels, which gives additional reason to assert the possibility of their synthesis.

The concept of history is not identical to the concept of continuity. History is broader than continuity. History is an interweaving of evolutionism and leaps. In the sphere of historical space, we discover the same dialectic of continuity and discontinuity as in the field of physical and architectural spaces.

Examples of historical combinations in modern architecture are new buildings next to old ones. Due to their spatial proximity, these different structures effectively emphasize each other's uniqueness by contrast. "The true effect lies in the sharp opposition; beauty is never so bright and visible as in the contrast" 42(N. V. Gogol).

A striking example of the synthesis of traditional and new architecture is the work of the Japanese architect K. Tange. Le Corbusier's student transformed old Japanese traditions into ultra-new architectural solutions.

Essays on the History of Architecture by Antithesis

In this section, presented as experimental historical essays, the author suggests looking at the history of architecture from the separate perspectives, each of which is set by a specific and irreducible architectural opposition.

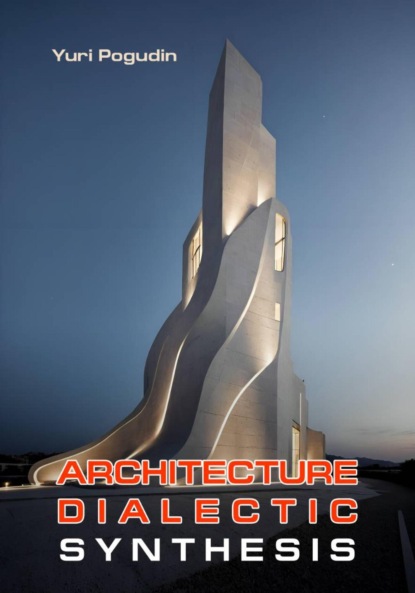

Cubicity – Sphericity / Straightness – Curvilinearity

Sphericity relates to cubicity in the same way that identity relates to difference. Sphericity is the state of a form when all its parts are so identical that it is no longer possible to distinguish any parts on the surface of the form. From the absence of parts, it follows that a spherical form is a pure identity that has no internal boundaries. The ball is infinite for an ant crawling on it, although it is finite for the person holding it in his hand.

The geometrically modified boundary category is an edge. An edge is what divides a form into distinct parts and makes it differentiated. A form containing edges, and therefore faces, is a difference from the point of view of eidos. It's a cubic form.

Thus, a spherical form is a single surface in which we cannot distinguish parts (faces), since we have no edges (borders). The cubic form is quite clearly composed of several clearly distinguishable surfaces.

The synthesis of sphericity and cubicity (facetedness) is a form containing both sphericity and cubicity. This form, on the one hand, is spherical, streamlined, and has no edges, and on the other hand, it is divided into distinct faces. Dialectics strives to preserve the subject as a whole and therefore insistently reminds that any sides, aspects, predicates, etc. of any subject are both identical and different at the same time. An object is a synthesis of its sides, properties, etc. in one indecomposable unity.

The limiting expressions of sphericity and cubicity in the geometric domain are, respectively, a ball and a cube. The ball is a pure identity, since it has the same curvature at all its points, and is completely identical to itself in any spatial position, absolutely symmetrical with respect to any axis passing through its center. The cube perfectly expresses the principle of facetedness, since all its adjacent faces are perpendicular. Perpendicularity is the ultimate degree of difference between two or more straight lines and planes. Any other angle between straight lines or planes will be their convergence, which tends to complete coincidence of the elements (at an angle of 0 or 180 degrees).

Let's give examples of cube and sphere synthesis:

1) a cube made up of balls or a ball made up of cubes

2) a straight cylinder with a height equal to the diameter of the base (one of its orthogonal projections coincides with the projection of a ball (circle), and the other with the projection of a cube (square)

3) the eighth part of the ball is the most complete synthesis (from the one side, an exact cube, and from the other, an exact ball)

4) all the countless complex stereometric forms with rectilinear and curved surfaces

The antithesis of sphericity and cubicity becomes especially intense when we take it in its mythological aspect. Sphericity is a property directly visually and mythologically attributed to the sky, as evidenced by such a stable expression as "celestial dome". Both the physical and spiritual sky possess the property of "globularity". "… The world of bodiless powers, or the Heaven, is a sphere that has a straight line around it <…> We look at the Heaven so that the Sun is between it and us. Therefore, we look at the Heaven from God's side. It is quite understandable that it appears to us as an overturned Chalice. The Heaven is a Chalice not because it seems so to our subjective gaze, but it seems so to us because the Heaven, in its inner and most objective essence, is nothing but a Chalice.43"

If the heaven is a chalice, then what is the earth? According to the principle of a simple opposition, the earth is a cube. According to A. F. Losev, the ancient Greek thinkers associated the element of the earth exactly with the cube44. The body is an earthly, earthy principle in man (Adam was created from the earth), and therefore "the whole body, made up of individual members, is square.45" The body is square not in appearance, but in the sense of its relation to the spirit, expressed geometrically.

Thus, within the spherical nature itself, we find both sphericity (heaven) and cubicity (earth). According to this division, the antithesis of top and bottom appears in the building: the roof, which interacts with the sky, and the foundation with the walls, which determine the interaction with the earth. It is easy to notice that most roofs and ceilings in the "old" architecture of different styles and eras are often spherical (domes, arches, cones, etc.). Both the Pantheon and St. Sophia of Constantinople are covered by a spherical form. The lower part of buildings, on the contrary, is solved as faceted, cubic. This correspondence of the bottom of the building to the cubic form, and the top to the spherical form, is probably partly due to the round shape of the human head – the upper part of his body. In ancient Russian architecture, there was a direct associative correlation: the dome is the helmet of a warrior hero.

The antithesis of "ball-cube" has a deep philosophical significance. It geometrically expresses the semantic opposites "nature-technology", "heaven-earth", "spirit-body".

In this regard, it is possible to suggest a classification of architectural structures. An orthogonally parallel structural system – a rack-and-beam one – corresponds to the cube. Arched, vaulted, shell-shaped structural systems correspond to the ball.

The struggle between the cubic and the spherical permeates the history of architecture. In the history of classical architecture, these trends were most obviously crystallized in the rationality of Classicism and the emotionality of the Baroque, which became a ramification of Renaissance synthetism. An example of the synthesis of these styles is the Palace Square in St. Petersburg.

In modern architecture, this struggle is even more acute, on the basis of which A. V. Ikonnikov argued that "it was only in the architecture of the twentieth century that trends emerged that focused on one of the polarities that had always previously acted inseparably.46"

The cubic form is often correlated with the technical one, and the spherical form with the natural, bionic one, although this correlation is optional. The architecture of Antonio Gaudi may serve as an example of the second case. One of his most famous works, the Casa Milà in Barcelona (1902-1910), is characterized by its "naturalness", smoothness of lines, curves, and fluidity of form. This is an example of Art Nouveau architecture, tending towards natural, curved outlines.

In German architecture of the 1920s, the "struggle between cube and ball" was expressed in the confrontation between neoplasticism (Theo van Doesburg, Piet Mondriaan, Gerrit Rietveld) and expressionism (Erich Mendelsohn, Hans Poelzig)47.

This antithesis can also be traced in Soviet architecture – in the difference between the design methods of constructivists and rationalists. "Constructivist buildings also reflect orthogonal drawings in their style, and there is little plasticity in them. The works of rationalists are more plastic, often there are no facades at all that could be drafted in orthogonal drawings.48"

Ivan Leonidov is a non-typical constructivist. "Back in the late 20s and early 30s, Leonidov used forms with a second-order generating curve, shell vaults in his projects along with rectangular prismatic volumes…"49.

Expressionism has become a relatively synthetic trend in modern architecture, one of the representatives of which is E. Mendelsohn. "Unlike the orthogonal, monochrome solutions of the modernists, Mendelsohn uses the contrast of orthogonal forms with curved ones.50"

In the history of architecture of the twenty-first century as a whole, there is a strong bias towards complicated curved forms, accompanied by criticism of modernism51.

Let's move on to the next point of the architectural form – let's consider it not only by itself, but also in relation to the otherness of space.

Massiveness – Transparency / Closeness – Openness

The dialectic of form as such, in itself, is outlined by the antithesis "sphericity – cubicity". The next point of logically consistent thinking of a form should be its correlation with space, and this correlation is when we are also interested in the form itself. This point is revealed by the antithesis "massiveness – transparency".

And here we find three fundamental relations of form and space – their identity, their difference, and, finally, synthesis.

What is the identity of form and space? This means that space and form communicate and mutually penetrate each other completely unhindered. Space encompasses the form and enters into it, and the form stays in space and encompasses it. This is possible only if the form is thought of as loose and unsaturated, absolutely transparent and permeable. But this means that the form is represented only by its outlines, borders, and edges. It is a form built exclusively of edges, filled with nothing but space, elaborate and open to external and internal penetrations.

Even earlier than N. Ladovsky, who said his famous aphorism52, the sage Lao Tzu emphasized that the importance of a building is in the space for life and filling it. Space was the dominant element of ancient Japanese and Chinese architecture, as N. Brunov writes in detail53. Thus, the Japanese and Chinese pavilion houses organize a gradual transition from the mass of the building to the space of nature, as opposed to the sharp contrast of surroundings and architecture originating from Renaissance palaces.

In modern architecture, the fusion of form and space is achieved by means of form perforation and the widespread use of glass. Transparent glass is the only material that allows spaces and objects to be considered identical while maintaining minimal differences. Glass with mirror properties already visually prevents the environment from entering from the outside, but allows houses to dissolve into each other. The environment loses its clear boundaries, and its image is doubled and repeated tenfold by multiple reflections. Such interpenetration and mutual dissolution of objects in each other creates the illusion of overcoming the gravity and immobility of matter. It is a shimmering, pulsating medium where shapes blend and color each other.