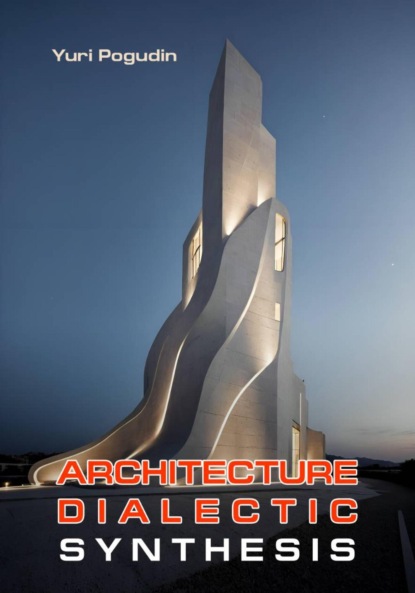

Architecture. Dialectic. Synthesis

- -

- 100%

- +

The second type of relationship between form and space is a difference. Taken to its utmost extent, it will give a form that is fenced off from the outside space, self-contained, closed, and possibly opposing itself to the environment. Here, first of all, one remembers the thicknesses of the Egyptian pyramids and the walls of Romanesque castles. It's a massive form.

Finally, a synthetic way of relating form and space will be a form that is both massive and elaborate at the same time. It is both open to space and has isolated areas within it. In the history of architecture, there are examples of such solutions that have demonstrated the power of the combination of opposites.

The antithesis of "massiveness – transparency" correlates with the antithesis of relationship with the landscape. The openness of the form can mean a connection not only with an empty space, but also with a space filled with natural forms.

Let's recall the Mortuary Temple of Queen Hatshepsut in Deir el-Bahari. The powerful dynamic ramps of the building are energetically turning into ledges of natural rocks. The temple is clearly distinguished from its surroundings by the measured rhythm of the pillars of the porticos, and at the same time merged with it – to the point of literally cutting into the rock.

An example of the new architecture is the Sainsbury Center in Norwich designed by N. Foster (1977). Among other advantages of the project, one is interesting for our topic: "from the sidewalls, one can look through the huge building, as though merging with nature. From other points of view, the laconic outline opposes it. The huge portals of the ends of this supershed, framed by trusses, are literally open to nature. They serve as a kind of frame, the backdrop of beautiful landscape paintings, and the external space rushes through the giant structure with a roar, imparting unexpected dynamism to its statics."54

Jean Nouvel demonstrated unexpected identifications and syntheses of the massive and transparent, architectural and natural in a number of his works. In the Soho Hotel in New York's Broadway (2003), "transparent, semi- and not at all transparent give rise to "transit effects", the transition of one into another, as a result, the building seems massive or permeable depending on the time of day, the weather … – the impression of instant dematerialization, the appearance and disappearance of matter.

A more sophisticated stage is the dissolution into the landscape, nature… The Museum of Ancient Cultures on the Quai Branly in Paris (2001) is fused with an exotic natural environment, you forget about its man-made nature… At the Guggenheim Museum in Tokyo (2001), architecture in general seems to be absorbed by nature – a hill in flowering trees, and the exhibition spaces inside, stained glass windows are masked in the folds of the relief… The seemingly fantastic formula has been realized: the invisible architecture turns out to be the most impressive.55"

The two antitheses of developed by us, sphericity vs. cubicity and massiveness vs. transparency, mutually intersect in a broader antithesis of architectural form versus natural form. The history of architecture has witnessed two opposing trends. One tries to connect architecture with landscape. The synthesis model was developed by the same Japanese and Chinese architecture, which organizes a complex spatial proportion: the main room of the building correlates with the surrounding bypass connecting it to the outside space, just as the whole building correlates with the garden connecting the house and nature. Both the architecture and the garden are dominated by a curved line.

The opposite concept to this approach is the contrast of form and environment. It was followed, for example, by Ivan Leonidov, who believed that the new city (Magnitogorsk) should cut into a green massif, contrasting with the surrounding nature by the geometricity of its layout and the rhythmic row of glass crystals of multi-storey residential buildings dominating other buildings forming a rationally organized network of servicing institutions56.

Architecture in this concept is opposed to nature as something rational and orderly to irrational and chaotic. In this contrast, a side of the essence of architecture is expressed. Man strives to overcome the chaos of natural forces, to crystallize and strengthen a certain stronghold in the sea of circulation and spreading of natural phenomena. "The city becomes an image of … a world completely created by man, a world more rational than the natural one… The rational is thought of as "anti-natural."57 The image of St. Petersburg is illustrative in this regard. "If we take old Petersburg, then the cultural image of the military capital city, the utopian city, which is supposed to demonstrate the power of the state mind and its victory over the elemental forces of nature, will be expressed in the myth of stone and water, firmament and mud (water, swamp), will and resistance.58" This understanding of architecture was very characteristic of the Renaissance and utopias.

Architecture is the design of oneself, one's own physicality, and the surrounding space. Architecture is the self-organization of society, it is the desire to get used to the natural world, make it your own, organize yourself in it and organize it according to yourself.

The moment of confrontation with nature is also associated with another one, the opposite, which consists not in conquering, but in the peaceful development of nature. The task of architecture, Hegel argues, as a "symbolic" art, is "to work out the external inorganic nature in such a way that it becomes related to the spirit as an artistically appropriate external world.59" The task of architecture is to overcome the conflict between nature and man, making nature related to man and man related to nature, and removing the opposition between them. The purpose of architecture is to make nature dear, kindred, close, instead of hostile and threatening, to humanize it.

Meter – Rhythm / Regularity – Randomness

First of all, let's notice the connection between the categories of rhythm and meter with the previous antithesis. The meter is a symmetry expanded into a spatial series, and the rhythm is an expanded ordered asymmetry. From this we can immediately conclude that rhythm and meter are opposites, like movement and rest.

What are rhythm and meter?

Rhythm and meter are, first of all, a certain separation, discontinuity. However, discontinuity alone as a complete isolation of moments is unthinkable. Rhythm is precisely such a discontinuity and such a set of isolated elements, which, without ceasing to be itself, is and is perceived as continuity, integrity. Rhythm is the organization of discontinuity as integrity. How does this happen? If the rhythm (meter) is originally a separation, then it has no reason for continuity in itself. What makes the rhythm be exactly series, and not a chaotic set, is the extra-rhythmic principle of integrity, in which isolated elements merge. This is a regular pattern. A regular pattern is an arrangement of separate parts in which they, while remaining isolated, merge into one whole. This means that it is possible to logically, regularly, and not randomly or arbitrarily, move from any element of the series to the adjacent, next or previous one.

The metro-rhythmic series consists of elements and inter-element intervals. Either one or the other can be rhythmized (then we have peculiar syntheses of meter and rhythm), or both parameters together (this is pure rhythm). The meter is obtained if both elements and intervals are unchanged. Rhythmization, that is, the organization of disparate parts into a logical sequence, occurs due to the principle of regular patterns, which consists in the fact that each subsequent element or interval of a series is modified by a certain constant coefficient (constant). Arithmetic and geometric progressions may serve as an example.

By itself, that is, objectively, the rhythm is given entirely and immediately, since spatially it exists at each of its points simultaneously, no element is either earlier or later than the other. But for the perceiving subject, the rhythm is given at some discrete point, and for its perception it presupposes the movement of the subject in time with a consistent coverage of the rhythmic series.

Let's summarize the definitions. Rhythm is the determinism of the constant formation of elements and inter-element relationships, presented in an orderly series, given in itself as an actual thing that has become and as a potential becoming perception of the subject. In the rhythm, the same eidos hypostatizes differently each time, but the steps of its hypostatization form a regular pattern. Rhythm is the ordering of unequal elements of the actual set of a single eidos, functioning in this set as a difference in both space and time, and each time with a different degree of intensity, which either decreases (slowing rhythm) or increases (accelerating rhythm).

Meter and rhythm together – metrorhythm – are ways of regularly organizing elements and relationships. There are other unifying means that allow to avoid chaos and preserve the integrity of the form with an arbitrary combination of its parts60.

Symmetry – Asymmetry

V. Krinsky wrote that "the task was set to express dynamics. We considered this quality to be the most important feature of the new architecture, distinguishing it from the static forms of the old architecture.61"

Difference is movement, and identity is peace. The potential difference in an electric field causes a current, the difference in elevation levels causes the flow of water in a river, etc. In moral life, movement – the will to moral perfection – arises as a result of the difference between the ideal and the real state of the soul.

We find the same regular pattern in the field of architectural form.

The difference is the reason for the movement. Let's translate this into the language of geometry. The identity of forms with respect to an axis is the symmetry of forms with respect to that axis. If the forms are not different from each other relative to the axis, they repeat each other, then they do not cause the form movement. The observer's gaze, discovering the sameness of the sides, calms down and does not move. The opposite of this is asymmetry. Here we see a difference in forms, their inequality to each other, which causes a desire either to balance them or to find a reconciling form that removes the difference between them – in a word, there is movement (both of form and gaze). The asymmetry must be associated exactly with the difference. After all, there are no single points, lines, planes in the asymmetry, relative to which the asymmetry would be established. They can be found in many places.

Thus, symmetry and asymmetry are the geometric correlate of the semantic opposition of identity and difference and the physical opposition of rest and movement. Asymmetry is one of the main ways to convey the dynamics of architectural form in space.

Let's move on to a more thorough analysis of the concept of symmetry.

Symmetry is usually defined as the same arrangement of equal parts of a shape in relation to a third shape (for example, a point, line, plane), called an element of symmetry. In other words, symmetrical shapes are shapes that, with a certain change in their spatial position, coincide – they coincide, when they are identified (aligned) spatially.

Let's give a dialectical definition to this concept.

Symmetry is the ordering of equal elements of the actual set of a single eidos, functioning in this set as a difference in space and identity in time, at the same time – and with the same degree of intensity in all parts of the set.

Symmetry differs from meter in that the forms are given in it at once, simultaneously; it is the sequence that is given in meter (and rhythm), here there is a transition from one part to another, and not a one-time perception. Symmetry obviously differs from rhythm in that rhythm is an arrangement of unequal elements or intervals, while symmetry is an arrangement of equal elements. Rhythmic form is a form that becomes, moves. The rhythm cannot but have a direction, strive for something. Symmetry is self-contained and self-enclosed. "Symmetrical compositions are characterized by strict unambiguity in the placement of form details and their unconditional subordination to the whole. It is no coincidence that symmetry was actively used to embody the ideas of centralization and a strictly systematic world order.62"

There are the following basic types of symmetry:

1) Repetition (translational) symmetry

2) Reflection symmetry

3) Rotational symmetry.

Translation is an operation of identity on a shape, reflection is an operation of difference, since all points of the shape change places. Rotation is an operation of self-identification, there is both a repetition of the shape and a reversal of points. In various mutual combinations, these types of symmetry form more complex ones.

The synthesis of symmetry and asymmetry is presented by:

1) dissymmetry (symmetry in general and asymmetry in parts)

2) antisymmetry (symmetry in form and opposition in content)

3) diverse combinations of symmetrical and asymmetrical parts in one object.

Right – Wrong / Rational – Irrational

The entire culture of mankind up to the twentieth century was dominated by rational – regular, symmetrically organized – forms. The avant-garde of the twentieth century rejects symmetry and highlights asymmetry. But again, this is an asymmetry of symmetry: the correct, symmetrical parts are asymmetrically organized into a whole. At the end of the last century, Frank Gehry made a new shift in architecture, opening up a whole world of irrational forms and combinations to modern architecture, which became possible with the help of computer modeling. The Guggenheim Museum Bilbao (1997) signals a profound change in the mentality of humanity.

I will present a few quotes about the irrationality of architecture of Frank Gehry from the chapter with the revealing title "Incomprehensibility" of A. V. Ryabushin's book "Architects of the Turn of the Millennium".

Unlike N. Ladovsky, who sought to use all architectural means to help a person navigate in space, F. Johnson admired the "spatial confusion" that is characteristic of the works of the intuitionist Gehry63. There is practically no "rectangular geometry traditional for modernism" left in his works.… Horizontals as such are absent, the rigor of verticals is minimal – a kind of compression and interpenetration of beveled and curved volumes and forms, a combination of multi-inclination sections and cuts, now straight then gently or vigorously bending protrusions and falls, various kinds of curvature spirals, creeping quasi-baroque arches of free outlines … The two exuberant sensual principles – baroque and deconstructive – are literally fused. However, it seems that the latter is by its nature a modern modification of the Baroque, which has always been atectonic and, in a sense, deconstructive" (about the Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein, Germany, 1989)64. "The author was irresistibly drawn – and further away – from an orthogonal static coordinate system: from right angles and lines to curves of increasingly complex orders, from planes to multidimensional surfaces.65"

"…By the end of the 1990s, Gehry had found another spectacular compositional opportunity – a combination of "flying sculpturality" with traditional rectangular geometry.… This time saw the purposeful use of collision effects of opposing as if mutually exclusive geometries and materials.66" "In general, an amazing balance of organics and geometry, dynamics and statics, inclined, horizontal and vertical principles has been achieved" (about the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao)67. A certain new architectural culture is making its way through Gehry's creations68.

Verticality – Horizontality

This antithesis is one of the most important in architecture.

Space, despite its extent, is something whole, therefore, it includes identity and difference. The identity in space is its vertical dimension, directed from the earth to the heaven. Horizontality is formed as a difference between two dimensions, and there is the plane of the "earth". In the totality of synthesis, a vertical line and a horizontal plane form a synthetic three-dimensional space.

The general structure of the form in space, its otherness in space, is something that must be understood through verticality and horizontality. In the modern theory of architectural composition, there are three concepts between which one can see a dialectical connection. These are three-dimensional, frontal and deep compositions and three types of otherness of the form in space corresponding to them.

In a three-dimensional composition, as a rule, the vertical form dominates. This is an overall vertical form designed to be perceived around itself. The frontal form is generally horizontal and is perceived by one-dimensional movement along it or towards it. The deep form is presented in full force and combines both volume and frontness, at the same time being fundamentally new and irreducible to the opposite types of forms forming it.

Thus, let's correlate three types of compositional form with three types of spatiality:

1) Volume (verticality)

2) Frontality (horizontality)

3) Depth (three-dimensionality)

If drawing and visual art in general on a plane aim to create the illusion of three-dimensional space in two-dimensional, then architecture, by analogy, is creativity in the three-dimensional space of a four-dimensional space. Profundity, depth, interior (as the receptacle of the human body) is the fourth dimension of architectural existence, which fundamentally separates it from both painting and sculpture.

From the point of view of movement, the antithesis of vertical and horizontal is synthesized in the diagonal. Moving horizontally, we don't move vertically, and vice versa. And when we move diagonally, we move both horizontally and vertically. Motion in these planes is uniform, if the diagonal is inclined to the vertical plane at an angle of 45 degrees. By changing this angle, one can also change the ratio of the amount of movement vertically and horizontally.

Perhaps, feeling precisely this dynamic synthetics of the diagonal, K. Melnikov attached such importance to it: "One of the strongest dimensions of architecture is the diagonal.69" "My best tools were the symmetry outside of symmetry, the boundless elasticity of the diagonal, the full-fledged thinness of the triangle and the ponderable weight of the console.70"

Combining the vertical, horizontal with equal bases and the diagonal gives an isosceles right triangle. Two of these triangles can form a square, and twelve can form a cube, which can be considered as a model of a three-dimensional space built on horizontals and verticals. In the search for a synthesis of all three mutually orthogonal directions of space, we will again come to the diagonal – the diagonal of the cube, the movement along which is movement simultaneously in all directions. The diagonal form in architecture is the most powerful means for expressing the dynamics of space and creating a sense of its three-dimensionality. The horizontal and vertical do not have this property, because the movement is one-dimensional in them. A diagonal is a three-dimensional movement in three-dimensional space.

The antithesis of horizontality and verticality was most clearly manifested in the contrast of the general spatial structure of pagan and Christian churches.

When looking at the first ones, the significant predominance of the horizontal development of the form over the vertical one immediately stands out as their distinctive feature. Thus, the composition of an ancient Egyptian temple is built strictly along a longitudinal axis, on which the entrance pylons, peristyle, hypostyle, sanctuary and other rooms are strung in turn. It is interesting to note the overall impression produced by the interior space as the visitor moves deeper into the Egyptian temple. "Natural optical perspective always reduces objects, but here the perspective effect was exacerbated by the rhythmic reduction of distances along the main axis, and the viewer standing in front of the first pylon felt the boundless depth of the suite. The large square courtyard began as a suite of interior spaces. The courtyard was flooded with sunlight, as the colonnades stood only against the walls, and the central axis was marked by free-standing columns. But when the viewer passed through the second pylon, he found himself in a completely different environment. It was the so-called Great Hypostyle Hall. The brilliance of the sun was replaced by semi-darkness here, as only the central passage was illuminated through high-cut latticed windows, while the sides of the hall were devoid of natural light. <…> The further the viewer moved along the longitudinal axis of the Karnak temple, the smaller the pylons blocking the way became and the halls became narrower, and finally, in a distant and almost dark small sanctuary, the golden boat of Amon shone in the light of the flames.71

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «Литрес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на Литрес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Примечания

1

Quoted after: Ryabushin A. V. (2014) Arkhitektory rubezha tysyacheletiy [Architects of the Turn of the Millennium]. Book one: Lidery professii i novye imena [Professional Leaders and New Names]. Moscow: Iskusstvo – XXI vek. – p.221. (in Russian)

2

The twenty-meter-high and sixty-meter-long Great Sphinx of Chephren shows the relativity of the difference between architectural and sculptural forms in terms of size (note mine – Yu.P.).

3

Losev A.F. (1995) Forma. Stil. Vyrazhenie. [Form. Style. Expression]. Moscow: Mysl. – pp. 122-123. (in Russian)

4

Mastera sovetskoy arkhitektury ob arkhitekture [Masters of Soviet Architecture about Architecture], vol. 1. (1975) Moscow: Iskusstvo. (in Russian) – p. 344.

5

Losev A.F. (1995) Forma. Stil. Vyrazhenie. [Form. Style. Expression]. Moscow: Mysl. – p. 124. (in Russian)

6

Losev A.F. (1999) Lichnost i absolyut [Personality and the Absolute], Moscow: Mysl, – p. 381. (in Russian)

7

Losev A.F. (1999) Lichnost i absolyut [Personality and the Absolute], Moscow: Mysl. – p. 243, 411-412. (in Russian)

8

Losev A.F. (1995) Forma. Stil. Vyrazhenie. [Form. Style. Expression]. Moscow: Mysl. – pp. 122. (in Russian)

9

Florensky P. A.(1999) Works in four volumes, vol. 3(1). Moscow: Mysl. (in Russian)

10

Updating these comparisons in accordance with today's technological developments, we can say that an air conditioner corresponds to the lungs, video surveillance systems correspond to the eyes, a gas or electric stove, a microwave oven correspond to the digestive system, and a computer, of course, – to the brain .

11

Florensky P. A.(1999) Works in four volumes, vol. 3(1). Moscow: Mysl. – p. 415-416. (in Russian)

12

Losev A.F. (1999) Lichnost i absolyut [Personality and the Absolute], Moscow: Mysl, – p. 442-443. (in Russian)

13

Florensky P. A.(1999) Works in four volumes, vol. 3(1). Moscow: Mysl. – p. 416. (in Russian)