- -

- 100%

- +

The day dawned magnificently today. A cool breeze blew, the grass swayed peacefully. Somehow, all the discomforts of the journey over rough hills and wooded valleys were immediately forgotten. Yesterday towards evening we reached a creek, which we couldn’t cross for a long time, moving along its bed. The horses moved with great effort, pulling their hooves from the root-tangled bottom. In the end, we crossed to this side and immediately made camp.

It must be noted that the Great Plains look quite different now than they seemed from the steamboat. Then I saw much greenery, which is natural, since I was traveling upriver. Now the prairies are a continuous yellow carpet. The tall grass is mercilessly scorched by the sun. A solitary poplar or a small grove immediately catches the eye, their green crowns perfectly visible against the yellow grass.

Keith, as usual, rose before me and was already making coffee. He makes coffee, as is customary here, that is, he roasts it haphazardly in a pan and brews it with river or rainwater in our only kettle. That is, he has another six or more kettles in his wagon. But he doesn’t touch them, saving these shiny vessels for trading with the savages.

The fight

The Indians dismounted and dropped into the tall grass, each laying out bags containing headdresses, paint in pouches, and sheathed weapons nearby… A few minutes earlier, the scouts sent ahead had returned and reported a small enemy party. The Ptarmigan people estimated when the enemy would be within immediate reach and began preparing for battle without haste. Hands scooped up paint. Now their faces would lose their own features, and the evil spirits would not be able to recognize them if any of the warriors died and tried to drag the fallen to the underworld. Many covered their faces completely with a thick layer: some blue, some yellow, some white. Some painted their faces in halves with different colors. Each had his own principle, corresponding to his inner voice. Chests, bellies, arms, and legs were also covered with patterns, according to the command of their guardian spirit. The paint was meant not only to frighten the enemy. Each new face, laid over the real one, necessarily held a hidden power that protected the warrior from enemy arrows.

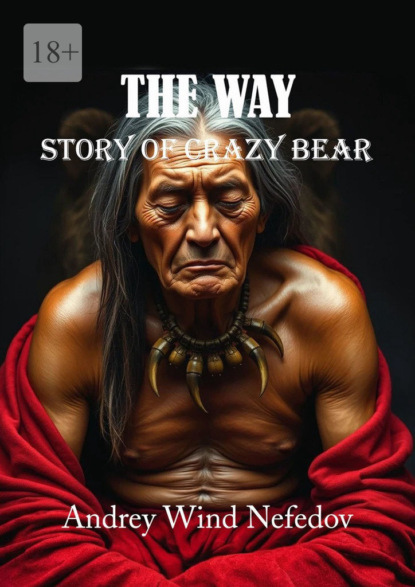

Bear put on the mask of his protector, its fangs hanging low over his eyebrows. Two hawk feathers were attached to the left bear’s ear. Bear’s face was entirely covered in blue, except for his nose, lips, and lower jaw…

Unexpectedly for all, Beak raised his hand and said:

“I will die today. Our enemies have more power than we do. They carry the flying iron of the white men. Do not strive to overcome them, but I must strike down their leader. Now I will sing my death song, and you will smoke me with the smoke of sweetgrass.”

“Why do you think they have flying iron?” asked Three Fingers, surprised.

“I know, I had a vision,” Beak said quietly, without opening his eyes or raising his head. “Only Bear can take part in this fight. He never looked back once during our journey, so no cunning spirit could latch onto his gaze and follow him. He slept only under his own blanket, and no evil spirit seeped unnoticed into his body at night to bring him a foreign weakness that exists in each of us. And some of you used a common blanket. And also… Bear has a strong protector. I do not know who it is, but a rare fighter receives such protection. Bear can take part in this fight. The rest should only frighten the enemy…”

Less than half an hour passed, and the Indians, holding their ponies back, rode up the hill in a single line. The enemy party should have been approaching the opposite slope by now. Beak let out a guttural cry, and the riders, covered in bright paint, surged over the hillcrest together. About a hundred meters away, the Psaloka – the Crow People – were riding at a leisurely pace. Like the Ptarmigan, there were ten of them, all stoutly built, confident after a successful raid on someone’s camp. They were dressed in ceremonial attire and had painted their faces black. Ahead of them moved a herd of about fifty horses, and these very horses prevented Beak’s party from launching a lightning attack. The herd milled in place, frightened by the loud cries of the attackers.

Beak furiously beat away the strange horses darting around him and pushed towards a rider in a magnificent headdress, whose long train slithered almost on the ground with every sharp movement of his horse. This rider raised both hands above his head with a loud cry, and a polished long-barreled rifle flashed in the sun. From behind the leader, a warrior shot out, rearing his spirited horse; on his head sat a stuffed falcon with spread wings. He already held his rifle aimed at the Ptarmigan, and a second later a shot rang out loudly, spreading waves of bluish smoke around the savage. Someone to Beak’s right gasped and leaned heavily, barely staying in the saddle. Beak glanced briefly at the wounded tribesman and turned his gaze back to the enemy in the huge headdress. Before his eyes were hands covered in black paint, greasy marks imprinting the shiny rifle barrel as the Indian brought the stock to his shoulder. A moment stretched into eternity. Now the bottomless muzzle of the barrel leveled with Beak’s eyes, then by inertia dropped slightly lower. And then the world went mad again, hooves pounding the ground deafeningly. Fire sprayed into Beak’s face. A close-range shot slammed into his ears. In a fraction of a second, the panorama was shrouded in thick smoke. Beak felt as if a part of his body had detached from him, as if lost. Then it became hot right under his throat. From the outside, he saw himself sitting on his horse very crookedly, leaning far back and looking up. And then Beak screamed piercingly. With this insane cry, he dragged himself back from the abyss of death like with a rope, clenched a club with three blades at the end in his hand, and, bursting through the powder smoke, found himself right next to the Psaloka leader. The raised sharp weapon descended swiftly upon the enemy, and its three steel teeth sank into the hot flesh.

Bear saw Beak plunge the mighty club into the back of the rider with the rifle and, falling from his horse, drag the enemy with a broken spine down with him.

From the rising dust emerged a slender man of black color. The horned buffalo scalp fitted to his head stretched its hair down his back, seeming to grow into the man’s skin. The rider sat easily on a glossy jet-black stallion and pranced before Bear. In his hand was a long spear with locks of hair dangling near the tip and many small skins tied along the shaft. The rider looked back; on his entirely black face, eyes flashed and a snow-white grin of teeth appeared.

Bear directed his horse towards him, and Bear Bull – for it was he – nodded his head approvingly, as a real bear sometimes does, opening its mouth and nodding its shaggy muzzle. Then the rider burst into motion, becoming a blurry shadow. He tilted his horned head so low that it merged with the head of the black horse, and for a moment, to Bear – the only person on the battlefield who could see the black rider – it seemed that his protector had turned into a huge bull.

The Indian raised his bow, placed an arrow on the string, clenched three more in his teeth to save time searching in the quiver, and raced after the shadow-rider. He saw him jab the nearest Psaloka with his long spear and gallop on. Bear let fly an arrow and knocked down the enemy Bear Bull had marked for him. And Bear Bull stopped near Beak’s dead body and waited. Bear reined in his horse right where the ghostly horse had been trampling the grass. Easily lifting the old man’s body, he laid it in front of himself and started to ride towards his party. But the black shadow performed its mysterious dance before him again. A rifle from a dead Psaloka gleamed in the grass, and Bear had to take it. He scooped up the weapon without stopping his galloping horse, leaning out far and holding Beak’s body with his hand. A warning shout came from behind him. Bear turned and saw a broad-shouldered warrior on a spotted pony, its neck and rump covered entirely with red handprints, very close. The warrior held a spear in one hand and in the other a small pole decorated along its length with hawk feathers and a stuffed owl on the top end.

Bear drew the bowstring and barely released the arrow when the thick shadow of Bear Bull struck the heart of the rider with the staff, and the arrow loosed by the Ptarmigan warrior pierced the same spot.

Continuing their fearsome cries, the parties drew apart. Bear, straining his throat with all his might, spewed curses at his enemies and threateningly raised the picked-up rifle above his head.

Another shot cracked from the Psaloka side, and the Lakota galloped away.

Mato Witko

His Own Words

The Crow. This bird was revered by many tribes. Our friends, the Cheyennes, gave the names of these birds to a people who lived north of us, in a beautiful country with many snowy mountains. There was indeed something bird-like in these people. The Crow people called themselves Absaroka. We called this tribe – Psaloka.

We had been enemies with the Crow Nation for a long time. And in those years, war with them was our main business, because we penetrated deeper into their country every year. There were many more of us, Lakotas, than Psaloka, and we needed new pastures for our huge herds. Their warriors fought bravely against us if our parties did not outnumber them too greatly. They were worthy opponents.

But when the Lakotas first appeared in the country of the Psaloka, which was a very, very long time ago, all of our people died. Thirty men from the Crazy Dog society remained lying in a foreign land. Then many of our parties gathered together – the They-Sow-Beside-the-Water, the Scattered Ones, the Twice-Boiling – and went to the country of the Psaloka. I heard in my childhood from the old men that there was a fierce battle. Our people managed to destroy an entire Psaloka camp and took many prisoners. Since then, there has been constant war between us…

Yes, they were skilled fighters, and we remembered all the fights with them. This may seem strange to you white people, but we often counted the years precisely by the importance we gave to one or another military clash with the Psaloka. That summer remained in our memory as the Year-When-Beak-Bravely-Cut-Down-the-War-Chief-of-the-Psaloka. Other tribal groups had their own reckoning of time, they celebrated their victories and mourned their losses. But events important for our entire people, for all Lakotas, did occur. Then much more serious cases entered the tribal calendar. Thus appeared the Year-When-Many-People-Died-in-Convulsions, or the Winter-When-the-Stars-Fell, or the Winter-When-the-Snake-Village-Was-Destroyed. This was remembered by many, it shook many.

Today, nothing happens around me. One by one, those with whom I spent a long life are dying, and I must put them in the ground, as the white bosses at the agency command me. I cannot place the dead high on a platform so that the wind, sun, and rain turn the dead flesh to nothing. And I too, when my half-blind eyes close for the last time, will be nailed into a wooden box, lowered into a hole, and crushed with a stone. And I can do nothing about it. I am old and weak. But before, I was filled with strength. I was ready to fight without rest.

On the day of Beak’s death, we were all seized with sorrow, our hearts constricted with despair.

Beak had been a mentor to many youths in our party, so they stubbornly insisted that we take the body of the fallen to our village. If Beak had died in camp, the relatives would certainly have dressed him in a richly embroidered shirt, wrapped him in hides, and suspended him on high poles. But those killed in battle, if the journey home was not short, were customarily buried where they died. Therefore, Lame Wolf and Red Marten, as the eldest among us, decided to leave him here. We only moved his body to a steep, wooded mountainside and there built a small platform of branches, securing it to a spreading tree whose mighty trunk overhung a rocky gully. We thickly painted Beak’s face and hands with red ochre. On the platform, on both sides of the body, we laid all his weapons. We secured his shield near his head. At the base of the tree, we set up a small shelter where relatives could sit when they came to mourn him. After that, we cut the throat of the horse Beak had ridden during the fight and laid it on the ground right beneath the platform. I scooped up the pooled blood and smeared it on the roots of the tree. Three Fingers sprinkled tobacco around the tree.

Then we rode away. Laughs-Silently moved last, keeping an eye on Blue Arm, whom we had placed on a travois because a bullet had pierced his thigh during the fight.

The sun rose twice after that, and suddenly we saw a large wagon with two white men sitting high atop some sacks and boxes. The few Pale-faces who appeared in our lands usually used packhorses. A wagon was a novelty to us.

Yes, we rarely encountered the Light-Eyed in those years. We heard more about them. But once I saw white traders when I traveled south to our relatives who roamed near the Shell River. Where its waters flowed into the Turbulent River, there stood a log fort where the Lakotas sometimes came to trade.

Now people with white skin had appeared in our country. We were surprised seeing those two. Our blood boiled immediately. We had never had the chance to fight white people because they did not interfere with us. But this time, we grabbed our bows and clubs. We thirsted for revenge. Beak had forbidden us to fight those Psaloka, but no one had said we couldn’t kill the Light-Eyed.

My friends worked themselves into a frenzy with loud cries, making their horses spin in place, transmitting their excitement to them. Lame Wolf raised his hands to the clouds floating above us and began a brave man’s song.

I raised my palm to the long fangs of my bear mask and pierced the skin on the back of my hand.

“Oh, my brother Bear, make it so the flying iron of the Light-Eyed does not harm us. We have lost a good man. We can no longer call ourselves victors when we return to the village. Help us, my brother!” Such were the words I spoke while the bear’s fangs tore my hand.

Then Three Fingers rushed forward. He crouched low to his horse’s neck, and the white men could not hit him. But they immediately shot his pony. It seemed to me they did not want to fight; they looked confused. One of them wore a tall hat with a long, beautiful ribbon behind it; he was shouting something at us. But we had already started the fight. We were already flying side by side with the Spirit of Death.

Red Marten rode in from the side and with three arrows killed the man in the tall hat. The second Pale-face was doing something with his weapon at that time. I stopped right in front of him and had already drawn my bowstring, but the white man was suddenly blocked by the black, horned shadow of Bear Bull.

“Stop! You must save this Light-Eyed one!” my protector shouted to me.

The stranger

The rider closest to the wagon was clad in a feathered headdress, resembling a swaying crown. The round shield on his arm had a red border made of cloth bought or stolen somewhere, and it fluttered with the eagle feathers attached to it. Beside him rode an Indian with a bear’s head resting on his own, its fangs hanging right over the savage’s eyes. Behind them, other long-haired horsemen fanned out. Randall Scott had time to notice that some had fox skins draped from their shoulders to their chests, their paws brightly painted, with tufts of crow feathers dangling from the foxes’ muzzles.

“Don’t shoot!” shouted Keith Malbraid, glancing quickly at Randall, and threw both hands up, showing the redskins his empty palms. “It’s the Fox Warriors… better to handle this peacefully…”

At that same moment, with a frightening whistle, two arrows slipped past just above Randall’s head. A second later, another thudded loudly into the wagon’s side. Out of the corner of his eye, Scott saw it quivering, its sharp tip buried in the dusty board. The savages’ intentions left no room for doubt, and there was no time for thought. So Randall shot at the nearest rider, who was leaning to the side of his painted, maned mare, hiding from bullets. The horse tumbled, stretching its neck as it fell and breaking it, let out a terrible snort, and kicked its legs in the air. In the thick clouds of yellow dust kicked up by the thrashing horse, the Indian nimbly scrambled away on all fours, dropping his feathered headdress as he ran.

Then, from somewhere behind, a rider emerged, thickly covered in greasy white paint, shrieked something, and lightning-fast, released three arrows into the bewildered Keith. They stuck in a row along his spine, one under the other, like in a circus act.

The rising wall of dust, pierced by sunlight, filled with frantic shadows of men and horses. The paint on the savages’ bodies and their colorful ornaments merged into one huge, solid brushstroke. From this flickering bright mass, the figure with the bear’s head on its shoulders suddenly emerged. For a split second, it seemed to Randall that a real bear had appeared before him, drawing a taut bow. The arrowhead froze a few dozen centimeters from the white man’s chest.

Randall felt the arrow’s shaft rip through the air and strike him hard in the chest… He staggered but stayed on his feet… Something had happened… The arrow remained on the bowstring… The momentary vision of his own death receded; the deafness that had plugged his ears turned into a whistle and then back into the familiar noise – horses stomping, people shouting incredibly loudly… The bear mask held the bow drawn but did not release the arrow… Something was happening. It seemed the savage was confused. He was as if listening to someone and couldn’t believe what he was hearing…

Behind him and on both sides of the wagon, his excited tribesmen crowded, waving clubs and shields. The bear mask suddenly sharply lowered the bow and turned to them. In an irritated voice, this Indian shouted at the others and began waving his arm, as if shooing the riders away. They answered with indignant shouts. Someone raised a spear with a bundle of hair near its tip. But the man in the bear mask reared his horse and decisively moved against the indignant warriors.

“Hia! Hia!” he repeated, throwing burning glances over his shoulder at the white man.

The Indian whose mare Randall had shot had already taken the horses from the wagon and, clearly displeased with the bear mask’s behavior, bent over Keith Malbraid’s body. Two swings of a heavy club with sharp blades embedded in it were enough for him to sever the corpse’s head. With a triumphant cry, the Indian grabbed it by its red locks and, riding up close to Scott, shook the terrible trophy viciously. Blood ran down the savage’s raised arm and dripped from his dust-covered elbow onto his muscular chest, gleaming with grease.

Several savages were already rummaging in the boxes stacked in the wagon, throwing out colorful rags, sorting through glass beads, constantly uttering cries of delight.

Randall closed his eyes…

Suddenly, the Indians galloped away. One of them was sporting Keith’s tall hat with its dangling, bead-embroidered ribbon. The last to ride off was the man in the bear mask. Before disappearing behind a hill, he stopped and looked at Randall for a long time. His pony impatiently pawed the ground, raising lazy dust. Then he spurred away and was gone.

Randall collapsed weakly onto the slashed-open sacks. Consciousness was ready to leave him. The sky swelled above him, now sucking the snow-white clouds into some kind of funnel, now lowering them right to Scott’s face. At times, the sky became impenetrably black, and then the whiteness of the clouds became blinding, but after a few seconds, the azure returned and the world became familiar again. The settling dust smelled of horses.

That night, he covered Keith Malbrad’s headless body with dry earth and settled down under a blanket near the wagon wheel. Quite close to him, a steep cliff rose like a huge shadow, emanating a grave-like chill. Randall couldn’t sleep, the tension was too great. So he took a thick, leather-bound notebook from his duffel bag, undid the clasp on the thin strap, and began frantically recounting the events of the previous day. The reddish glimmers of the weak campfire floated over his tired face.

Closer to dawn, a distant shadow of a rider appeared in the murky gray air. On his head was the mighty muzzle of a bear. Seeing the terrible guest, Randall tensed his whole body. What could the strange savage’s return mean?

Randall Scott closed the notebook and stood up.

“What do you want?” he exclaimed, stretching out his hand holding the notebook in front of him.

The savage grew wary. The paleface was pointing his mysterious object at him and seemed to be shouting incantations. Perhaps it was a small square shield? Every shield carries protective power, and every warrior’s shield is different. The Light-Eyed One’s shield is strange, but special power lives in incomprehensible things – even the most experienced shamans are often powerless against it. The Light-Eyed One’s shield is strange. Its magic has roots in the unknown, which is why, perhaps, Bear Bull intervened for the white man.

The Indian shook his head. He would take the Light-Eyed One’s protective object, and then there would be no need to kill the foreigner – he would die on his own without his amulet. Having reached this conclusion, Bear raised his hands to the lightening sky and, without taking a weapon, urged his horse toward Randall Scott.

“I am not afraid of you! Look! I am not afraid of you!” he shouted in his own language, approaching the Paleface. His palms were demonstratively turned to the sides. Riding up close to Randall and circling him twice, Bear suddenly leaned down and snatched the notebook from Scott’s fingers. The next instant, he spurred his horse and galloped back, still with his arms spread, but now one hand clutched the Light-Eyed One’s mysterious thing.

Randall burst into curses. The savage’s behavior made no sense to him. He was ready to fight, ready to die, ready to have a long, tedious conversation using signs. But he did not intend to be an object of ridicule for painted natives.

“Damn you, you stinking scarecrow!” Scott bellowed. “If I ever catch you again, I’ll shove a rifle up your ass! I’ll feed you your own shit! I’ll pull a sack over your head instead of that bear face and hang you from the nearest tree!”

He stood alone in the middle of an endless, mountainous region through which he now had to walk on foot, walk to who knows where. He was a stranger, knew nothing, and now feared everything. He could have begged the Creator for protection, but he did not believe in God; he was used to relying only on himself, on his own strength. God remained a beautiful fiction to him, while the world around him always felt very real and often painfully so.

“And all this just because my damned hands can’t hold back in time! I just had to cheat at cards!” Randall desperately kicked the ground with the toe of his boot, raising a fountain of dust. He imagined himself in the midst of a noisy crowd on a town square, where shopkeepers chattered cozily and women’s heels clicked. Yes, a man cannot know where fate might throw him…

On the third day of his journey, dragging a huge bundle of provisions on his back, Randall realized his strength was exhausted. He had to pour out most of the contents of the sack, but even the little that remained at its dusty bottom pulled him toward the ground. At first, he tried to follow the tracks of the wagon he had arrived in with Keith. But the wheel tracks were lost by the evening of the first day. Now he wandered aimlessly. His feet constantly caught on stones and roots, the hot air wove complex patterns before his eyes, his dried-out throat felt swollen and stuck together.

In the evening, collapsing onto the ground, he discovered two motionless bodies about half a meter away from him, each with several long arrows sticking out. Small items were scattered around: pouches, bags, pieces of leather, wooden bowls, spoons. A little further away, Randall made out a large dog in the grass with its skull smashed.

“Devilry!” He winced, feeling nausea rising. The blood on the dismembered flesh and on the ground around had already dried, but it was clear the murder had happened very recently. A few crows hopped nearby, but vultures had not yet descended to begin their feast.