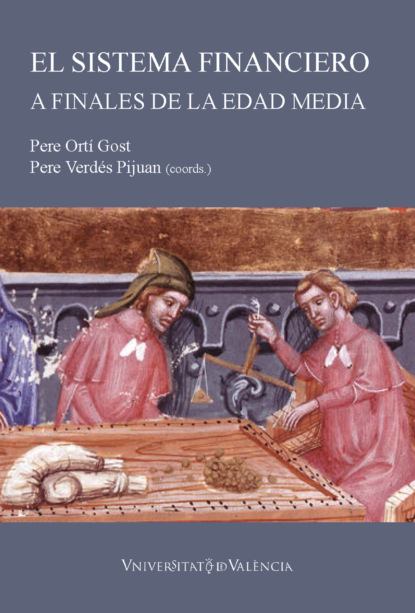

El sistema financiero a finales de la Edad Media: instrumentos y métodos

- -

- 100%

- +

Au terme de l’analyse, on est conduit à faire l’hypothèse que le prix payé pour acheter la rente traduit une sorte de valeur locale pluriannuelle du grain, antérieure à la confrontation de l’offre et de la demande. Il doit être distingué aussi bien du prix de référence annuel fixé à l’automne, qui est ensuite inscrit dans les apprécies des rentes, que du prix journalier constatable sur le marché, qui tient compte de la qualité de la marchandise et du rapport de l’offre et de la demande. C’est l’existence socialement reconnue d’une telle valeur qui fonde le statut du grain comme une monnaie alternative dans l’espace d’un marché local. En tout état de cause, l’existence d’un tel marché suppose aussi un niveau d’abondance et de régularité dans l’approvisionnement qui permette aux acteurs de s’assurer dans leur choix d’investissement. La constitution de ce marché résulte enfin d’une évolution de la stratification sociale. Un certain nombre des acteurs mentionnés dans les chartes ne sont pas eux-mêmes des cultivateurs (plusieurs sont des clercs) et le froment qu’ils s’engagent à verser annuellement provient d’autres rentes et redevances dont ils sont les bénéficiaires et non de leur propre travail. Par ailleurs, les sommes versées par les moines aux vendeurs de rentes ne sont pas négligeables et leur réinvestissement peut aider à l’augmentation du capital immobilier, en terres, bien sûr, mais aussi en maisons, moulins, pressoirs et autres installations de production.15 À partir de la fin du XIIIe siècle, l’instabilité monétaire croissante dut accroître la sûreté de cet instrument monétaire, dont la valeur libératoire ne dépendait pas de la politique du souverain. Ainsi s’explique sans doute la faveur dont ces rentes continuèrent à jouir jusqu’à la fin du XVe siècle au moins.

Les remarques qui précèdent exposent les résultats d’une enquête en cours, portant sur un espace régional important, mais limité et segmenté. Sa continuation et l’examen d’autres dossiers permettront de tester la validité des hypothèses présentées. Les marchés locaux faiblement interconnectés qui servaient de fondement à un système de crédit où les grains servaient comme monnaie alternative aux espèces métalliques ne sont pas pensable dans le système de subsistances fortement politisé que connaît la fin de l’Ancien Régime. Il est clair que de ce point de vue le système dont la description est esquissée ici diffère profondément des situations étudiées par Jean Meuvret dans son grand livre sur le commerce du blé à l’époque moderne.16 La géographie et la chronologie des situations décrites plus haut devra encore être établie, pour déterminer la date de sa mise en place et l’originalité éventuelle des campagnes normandes dans le contexte du royaume de France ou du Nord-Ouest Européen. Il nous restera enfin à comprendre comment a pu s’accomplir la transition d’une situation à l’autre.

ANNEXE 1

Thaon, novembre, 1246.

Vente par Nicholas Fauvel aux moines de Savigny d’une rente d’un sextier de froment à la mesure de Thaon, à prendre à la Saint-Michel de lui ou de ses héritiers sur sa masure de Thaon pour 4 lb. 15 s. t.

Paris, Arch. nat. L 976/679.

Nouerint presentes et futuri quod ego, Nicholaus Fauvel de Thaon dedi et concessi abbati et monachis de Savigneio pro quatuor libris et quindecim solidis turonensium quos mihi mi dederunt videlicet unum sextarium frumenti ad mensuram de Thaon percipiendum annuatim in masura mea de Thaon sita iuxta masuram Thome de Reviers ex una parte et iuxta masuram Willelmi de Lachon ex altera per manum meam uel heredum meorum uel cuiusque qui predictam masuram tenuerit, ad festum sancti Michaelis in mense septembri, tali condictione quod dicti abbas et monachi propter defectum solutionis prescripti sextarii frumenti in prenotata masura poterunt ac debebunt plenariam justiciam exhibere. Et ut hec mea donatio perpetue firmitatis robur obtineat presens scriptum sigilli testimomnio confirmaui, actum anno gratie m° cc° xl° sexto in mense nouembri.

ANNEXE 2

Thaon, octobre 1272.

Thomas Mordant vend aux moines de Savigny une rente d’un sextier de blé en septembre, assise sur son masnage et sur toutes les terres qu’il tient ou tiendra des religieux à Thaon et Camilly, pour un prix de 5 lb. 10 s. t. ; l’acte est passé en présence des vavasseurs de Thaon.

Paris, Arch. nat. L 968/919.

Sciant omnes presentes et futuri quo ego, Thomas Mordant, vendidi et concessi viris religiosis abbati et conventui de Savigneio per centum et decem solidis de quibus me teneo pro pagato, videlicet unum sextarium frumenti annui redditus percipiendum et habendum et jure legitime emptionis posidendum sibi et successoribus suis de me et heredibus suis in mense septembri ad mensuram de Thaon super masnagium meum situm apud Camilleum juxta masnagia heredum Rogeri Adeline et super omnes terras quas de eisdem religiosis teneo in territoriis de Camilleo et Thaone, sine ulla contradictione mei vel heredum meorum facienda. Et hanc venditionem et concessionem ego [et] heredes meorum tenemur predictis religiosis garantizare et defindere [sic] contra omnes. Et ut hoc sit firmum et stabile presentem cartam sigillo meo sigillavi. Datum anno domini m° cc° septuagesimo secundo mense octobri coram vavasoribus suis de Thaone et de Camilleo in curia eorumdem apud Thaon.

ANNEXE 3

Thaon, octobre 1266.

Thomas et Nicolas Lelégart, bourgeois de Caen, vendent aux moines de Savigny in rente de 4 sextiers d’orge pour 13 lb. 10 s. t. assises sur une série de terres décrites.

Paris, Arch. nat. L 976/876.

Sciant omnes et futuri quod nos, Thomas dictus Legat et Nicholaus dictus Legat, fratres et burgenses de Cadomo, vendidimus et concessimus et omnino dimisimus viris religiosis abbati et conventui Savigneio pro trindecim (sic) libris et dimidia turonensium de quibus nobis plenarie satisfecerunt, uidelicet quatuor sextaria ordei annui et perpetui redditus ad mensuram de Thaone, recipienda mense septembris quem predictum redditum Ricardus Gaufridi de Thaone nobis debebat in quinque acris et una virgata terre sitis in territorio de Thaone in tribus virgatis terre apud foveam Mapul, juxta teeram Henrici Boistart et apud turres Vigaren in dimidia acra iuxta terram Willelmi Alexandri et in quadam acra et dimidia virgata inter duas londas iuxta terra Petri Vernei et in dimidia acra apud Iubleiz iuxta terram Petri Vernei et in tribus virgatis apud parvam londam iuxta terram Abbatis Savignei et in dimidiam acram apud vallem iuxta terram abbatis Savignei et in medietatem quinque virgatarum terre iuxta terram Hosmondi Amelin apud Pirum et in una virgata in eadem dela iuxta terram Roberti de Rochela, militis et in una virgata in eadem dela iuxta terram Philippi Gaufridi ; in quibus predictis terris predictus abbas et conventus habebant prius quatuor sextaria frumenti et sextaria ordei duo et tres capones et tres panes tertion. annualis redditus per manum eius Ricardi, tenendum et habendum et jure legitime emptionis in perpetuum possidendum dictum redditum dictis abbati et conventui bene et in pace libere et quiete sine ulla reclamatione a modo nostrum vel heredum nostrorum, et nos predicti Thomas et Nicholaus et heredes nostri dictis abbati et conventui dictum redditum contra omnes homines garantzare et defendere tenemur vel in proprio feodo nostro si neccesse fuerit equivalenter excambiare. In cuius rei testimonio presenti carte sigilla nostra apposuimus, actum anno Domini m° cc° sexagesimo quinto mense januarii coram parrochia.

ANNEXE 4

Thaon, juin 1273.

Thomas Lelégart, de Caen, vend pour une durée de quatre ans à Roger de Hamars, bourgeois de Cean, une rente de 2 sextiers d’orge au prix de 13 sous manceaux (19 s. 6 d. t.).

Paris, Arch. nat. L 976/875.

Sciant omnes presentes et futuri quo ego, Thoumas Legat, de Cadomo, tradidi et concessi Rogero de Hamarz, burgensi Cadomensis pro tredecim solidos cenomanensium quos mihi pre manibus satisfecerit, uidelicet duo sextaria ordei ad mensuram de Thaun percipiendum annuatim apud Taun in quadam pechiam terre quam Ricardus Guiffroy de Thaun tenet de me in feodo et hereditate ; et ego predictus Thouma Le Legat et heredes mei volumus et concedimus quod predictus Rogerus de Hamarz et heredes sui faciant plenariam justiciam in predicta pechia terre sicut ego faciebam et facere debebam usque ad terminum quatuor annorum ; et ego predictus Thoumas et heredes mei predicto Rogero et heredibus suis predicta duo sextaria ordei usque ad terminum quatuor annorum tenemur garantizare et defendere et deliberare contra omnes. Quod hoc sit firmum et stabile ego predictus Le Legat presentem cartam meam sigilli mei testimonio confirmavi, actum anno Domini m° cc° lx° tercio mense junii.

ANNEXE 5

Évreux, 2 et 15 mai 1388.

Contrats de vente à terme de grains sur les marchés de Bernay et Brionne passés devant le tabellion de Bernay.

Archives départementales de l’Eure, 4E 45/7.

1. [2 mai] Fut present Gervés Cognart, de Saint Pierre de Granchamp, qui vendi a Clement Galey, demourant a la Coulture, II septiers de bley a comble bon et suffisant a la mesure de Bernay, II s[ous] le septier mains vaillant etc. a poier a II termes, moitié à la Toussaint prouchaine venant et l’autre moitié a l’autre Toussaint enssuivant ; obliga corps.

2. [15 mai] Fut present Jehan Le Febvre de Plasnes, qui gaiga a Gillot Le Roy, de Bonenay la somme de II septiers de bley au comble a la mesure de Bernay du meilleur de la blaerie dudit lieu, a poier l’argent que ledit bley pourra valloir au plus cher que il puisse estre dedens la Saint Cler [18 juillet] prouchaine venant, a la Saint Michel prouchaine après enssuivant ; obliga sauf le corps.

3. Fut present Johan de la Puille, de la paroisse d’Arclou, qui gaiga a Girot Le Roy la somme de I septier de bley a rais a la mesure de Brione, du meilleur de la blaerie dudit lieu, a cause de prest a paier l’argent que ledit bley pourra valloirs au plus cher qu’il pourra valloir dedens la Saint Cler prouchaine venant, a poier a la Saint Michel prouchaine venant, obligant sauf le corps.

4. Fut present Guerri Le Saige, qui vendi a Colin Le Roux, de Plasnes, I septier de bley a comble a la mesure de Bernay, II d[deniers] mains vaillant que le meilleur bley etc., a poier etc., dedens Noel prouchain venant, par XX s. t. dont etc.; obliga corps.

1 Laurent Feller (dir.): Calculs et rationalités dans la seigneurie médiévale: les conversions de redevances entre XIe et XVe siècles, París, Publications de la Sorbonne, 2009.

2 Vincent Corriol: «Redevances symboliques et résistance paysanne au Moyen Âge», Histoire & Sociétés Rurales, 37/1 (2012), pp. 15-42; en ligne:

3 François Neveux: «Villages et villes de Normandie à la fin du Moyen Âge: le cas des villages entre Caen, Bayeux et Falaise», dans Villages et villageois au Moyen-Age. Actes des congrès de la Société des historiens médiévistes de l’enseignement supérieur public. 21e congrès, Caen, 1990, París, Publications de la Sorbonne, 1992, pp. 149-160; Christophe Maneuvrier: «Les rentes en nature: un indicateur des systèmes céréaliers médiévaux? À travers les campagnes normandes», Histoires et Sociétés Rurales, 13 (1er semestre 2000), pp. 9-38.

4 Isabelle Theiller: «Prix du marché, marché du grain et crédit au début du XIIIe siècle: autour d’un dossier rouennais», Le Moyen Age, CXV (2009/2), pp. 253-276.

5 Ibidem, p. 257: «[…] quattuor modiis frumenti singolis annis reddendis in mercato Rothomagensi inter festum Sancti Michahelis et octauas Sancti Andree; frumentum autem reddetur a predictis priore et conuentu Prati predictis abbatisse et conuentui Sancti Amandi IIIIor diebus ueneris in mercato Rothomagensi singulis IIIIor mercatis unus modius ad pretium unius modii melioris frumenti IIIor sol. minus de unaquaque summa […]».

6 Paris, Archives nationales S 361 núm. 20 (bail du moulin de Voinles, mars 1279): «pro duobus modiis bladi videlicet uno modio frumenti ad sex denarios post melius bladum et uno modio avene bone et legitime reddendis et solvendis dictis decano et capitulo quolibet anno durante firma predicta apud Rosetum suis sumptibus et periculo et expensis videlicet medietate tam frumenti quam avene ad natale Domini et alia medietate ad festum nativitatis beati Johannis Baptiste».

7 Paris, Archives nationales, JJ 75, ff. 363v-364, núm. 600 (vidimus du roi Philippe VI enregistré à la Chancellerie en juin 1345 du jugement rendu à Caen le 1er août 1344): «Declaratoria quod presbiteri parrochie de Martrengny non tenentur soluere pro redditibus bladorum occasione hereditatum suarum nisi iuxta precium factum apud Cadomum de bladis regiis».

8 Bien qu’ils soient conservés en grand nombre, ces documents ont été rarement publiés; cf. cependant une apprécie pour la région de Carentan au début du XVe siècle éditée dans Documents du XVe siècle des Archives de la Manche. Catalogue de l’exposition organisée par les Archives départementales du 1 au 5 décembre 1998 et du 4 janvier au 2 avril 1999, Saint-Lô, Archives départementales, 1998, núm 26, pp. 75-77.

9 Je reprends ici l’analyse proposée dans Mathieu Arnoux et Gilles Postel-Vinay: «Territoires et institutions de l’assistance (XIIe-XIXe siècles): mise en place, crises et reconstructions d’un système social», dans Francesco Ammanati (éd.): Assistenza e solidarietà in Europa, secc. XIII-XVIII / Social assistance and solidarity in Europe from the 13th to the 18th centuries. Atti della XLIV Settimana di Studi, 22-26 aprile 2012, Florence, Firenze Universty Press, 2013, pp. 249-275, à partir des données rassemblées par Solène Jaugeat dans son mémoire de seconde année de Master: Études sur les rentes dans les établissements hospitaliers (Normandie XIIe siècle), EHESS, 2011.

10 Paul Le Cacheux: Essai historique sur l’Hôtel-Dieu de Coutances, l’Hôpital général et les Augustines hospitalières, depuis l’origine jusqu’à la Révolution, avec cartulaire général, 1re partie: L’Hôtel-Dieu (1209-1789), Paris, Alphonse Picard, 1895, p. XX.

11 Paris, Archives nationales L 968, L 970 et L 976.

12 Mathieu Arnoux: «Vavasseurs, dîmes et hiérarchies sociales dans les campagnes normandes (XIe-XIIIe siècles)», dans Cédric Jeanneau et Philippe Jarnoux: Les communautés rurales dans l’Ouest de la France au Moyen Âge et à l’époque moderne, Brest, Centre de Recherche Bretonne et Celtique, 2016, pp. 183-198.

13 Il s’agit de Thomas et Nicolas Lelégart (1266 et 1273), Roger de Hamars (1273), Guillaume Noé (1274).

14 François Neveux: «Villages et villes de Normandie», p. 160.

15 En 1260, les moines acquièrent de Thomas Macé un champ d’une acre dans la couture du «Long Boel» pour 9 livres, c’est-à-dire le prix d’un sextier et demi de froment de rente: Paris, Arch. Nat. L 968 (873).

16 Jean Meuvret: Le problème des subsistances à l’époque Louis XIV. Tome III: Le commerce des grains et la conjoncture. Texte, Paris, EHESS, 1988, pp. 97-143.

FOREIGN INVESTMENT IN PUBLIC DEBT IN THE NORTHERN LOW COUNTRIES, FIFTEENTH TO SIXTEENTH CENTURIES

Jaco Zuijderduijn Lund University

I

For many historians, polities’ capacity to borrow was crucial for the development of financial markets. Polities were usually among the most important borrowers in financial markets, and it has also been suggested they provided the investing public with a relatively safe haven for their savings. However, few studies have been able to establish how big the attraction of public debt was, and what effect this had on the redistribution of savings in emerging financial markets. This article asks to what degree public debt created by late-medieval polities helped to move savings from one place to another, and thus helped to bring together the supply of savings, and the demand for loans. To this end we focus on the geographic spread of creditors of several towns, and demonstrate how these towns managed to borrow from both citizens and non-residents. Late-medieval towns were not only active in local markets, but also had access to financial markets in their surroundings, and even those abroad. In theory such access to various financial markets should have brought about price convergence. To study whether this was the case, we also look at the interest rates polities paid on their public debt. Interest rates were quite similar, both towns, and even between towns and villages, which suggests that most polities had reasonably good access to at least several financial markets.

Interest rates on public debt gradually converged from 1300-1800: S.R. Epstein demonstrated a decline in interest rates in several regions of Europe, and more importantly, a convergence between these regions.1 This would suggest the existence of structures that in the long run helped to smooth spatial differences in supply and demand of savings. To be sure: why interest rates declined is still debated. Some scholars have suggested that this was due to an increase in coins per capita, at first because of depopulation in the wake of the Black Death,2 later because of improvements in silver production and due to increased mining activity in Central Europe, and the America’s after 1492.3 Others, following the seminal article by Douglass North and Barry Weingast on the English financial revolution, have claimed that interest rates could drop because improvements to the institutional framework of financial markets caused a reduction of risks and/ or the gradual integration of markets. Later, North even claimed that the level of interest rates is altogether the best indicator for the development of market structures.4 In this respect, some have also pointed at the gradual integration of financial markets, for instance due to the emergence of monetary unions.5 The latter views all assume savings were moved around more efficiently due to improved market structures.

A recent contribution to the latter strand of literature is David Stasavage’s study States of credit. Size, power and the development of European polities. Stasavage discusses one of the major puzzles of financial history: why did medieval city states and towns manage to borrow at lower cost than territorial states? He argues that the latter suffered from what we might call «diseconomies of scale»: due to large distances, it took relatively long to organize a meeting of the representative bodies responsible for debt management. In city states and towns, this could be done much faster, causing representatives to meet much more frequently. This allowed them to keep a close eye on public finance, which according to Stasavage made lending to city states and towns less risky. As a result these could borrow more and at better conditions than territorial states. Representatives of city states and towns also had a good reason to monitor public finance because they themselves were often major investors in public debt. These stakeholders thus had incentives to attend council meetings, and due to the low distances they had to cover, they could do this without much trouble. Stasavage’s main example is the General Council of Siena, which in the thirteenth century was also known as «Council of the Bell» because its members could simply be assembled by chiming a bell.6 Public finance, in Stasavage’s study, was a strictly local affair: polities borrowed from their citizens, investors lent to their city state or town. This may have been usual in polities such as Italian city states, where investing in public debt (via the so-called Monte loans) either was a privilege of citizens, or a duty weighing upon the wealthiest inhabitants, who were forced to lend.7 Under such circumstances the group of creditors indeed coincided with citizens. However, this was not at all the case in the late-medieval Northern Low Countries, where towns also borrowed from foreigners living out of town, and often even outside the province. Here, financial markets allowed for savings to be moved around, from places where supply was high, to places where demand was high.

Such «foreign investment» is important for our understanding of polities’ access to credit, and hence the way they were able to position themselves in negotiations with rulers. Since there were always far more savings available outside a polity than inside, a polity that was able to convince «foreign» savers to invest in its public debt could improve its political position. In doing so it might even achieve a comparative advantage over its competitors: the ability to borrow money from abroad may have allowed relatively small polities to match the financial muscle of larger polities. In this way the capacity to create public debt can be linked to processes of state formation: according to Charles Tilly access to financial markets allowed polities to negotiate rulers’ demands, and to receive privileges in return for funding.8 Also, polities’ access to financial markets has been regarded as a driving force in altering relations between rulers and subjects, and the emergence of supra-local institutions, such as parliaments where various polities cooperated in negotiating with rulers.9 To understand why over time some polities expanded, overtaking others in the process, it is important to look at to what degree they managed to attract «foreign funds» –and at what cost they did this–.

This article investigates to what degree financial markets in the late-medieval Northern Low Countries helped to move savings around from one polity to another. It also asks whether it feasible that this contributed to the gradual convergence of interest rates, by smoothing supply and demand. We will demonstrate that a considerable part of the creditors of towns in the Northern Low Countries consisted of «foreigners», and that these foreigners were usually among the more important investors in public debt. These were not citizens who could exercise direct control over their investments via participation in representative councils. Yet, they lend handsome sums of money to foreign public bodies at relatively low interest rates. This finding suggests that apart from the mechanism Stasavage described, and that allowed for investment by members of a polity, there were others in the late-medieval economy allowing for «foreign investment». These will be discussed in section II, providing an overview of the financial instruments used to move savings around, and the market structures that allowed for this. Next we proceed by studying foreign investment by looking at the geographic distribution of investors in public debt of the towns of Leiden in Holland (in the west of the present-day Netherlands), Groningen in the Ommelanden (in the northeast) and Nijmegen in the duchy of Guelders (in the east) (section III). We then proceed with the question of the efficiency of markets: did this moving around of savings contribute to price convergence? To get an impression of this we look at interest rates on the public debt of hundreds of towns and villages in Holland, in 1514 (section IV).

II

In the middle ages sovereigns, such as the kings of England, frequently borrowed large amounts, thereby relying on the services of Italian bankers. Rulers in the Low Countries did the same, borrowing not only from bankers but also from family members, fellow royalty, noblemen, and towns.10 However, besides this international system of «high finance» there were other ways to move money around, such as through the issuing of public annuities. Since the thirteenth century towns and villages in much of the Low Countries sold life annuities and redeemable annuities. Life annuities provided the buyer with a pension to be paid for the remainder of his or her life, redeemable annuities had to be paid until the principal was repaid, which was at the discretion of the seller. These annuities emerged in the North of France in the thirteenth century and quickly became a major type of funding in Northwest Europe.11 They allowed creditors to lend their savings to debtors on the payment of an annual premium that we today would call interest.12 In the late Middle Ages these became the instrument of choice of public bodies in the Northwest of Europe: in the Low Countries, the North of France, and the German Empire, towns and villages «borrowed» by selling life annuities and redeemable annuities.