El sistema financiero a finales de la Edad Media: instrumentos y métodos

- -

- 100%

- +

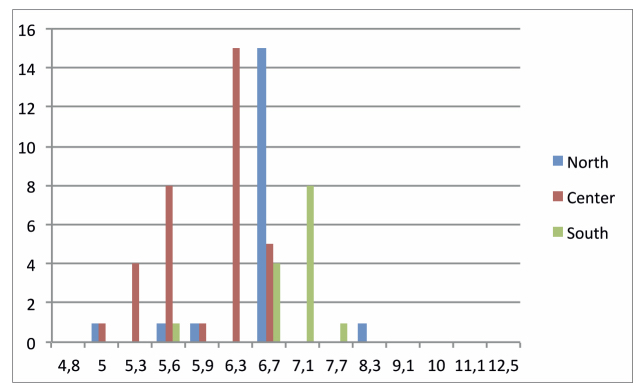

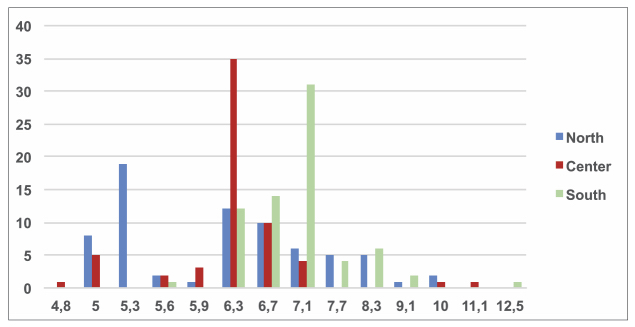

There were few differences between large and small towns: in the North all towns were small and interest rates did not differ much. In the centre the large towns Haarlem, Delft, Leiden, Amsterdam and Gouda in general paid interest rates ranging from 5,6 % to 6,3 %. They were somewhat better off than the small towns, which in general paid interest rates ranging from 5,3 % to 6,7 % (figure 4). Dordrecht, the only large town in the South, paid relatively high interest rates compared to small towns in this region.

When we take a look at the premiums paid by villages in different regions of Holland, it seems that differences were relatively low in the centre, and somewhat higher in the South (figure 5). In the North we clearly encounter the largest differences. This is the region above the River IJ, which was less urbanized than the other regions; Hoorn (3.600 inhabitants), Alkmaar (2.800) and Enkhuizen (2.300) were the largest towns.47 These were small towns; Holland’s six main towns, which all lay below the River IJ, had about 7.000 to 10.000 inhabitants.

FIGURE 4

Interest rates on redeemable annuities small towns (1514)

North: Alkmaar, Hoorn, Enkhuizen, Medemblik, Edam, Monnikendam, Beverwijk, Naarden, Weesp, Muiden, Purmerend. Center: The Hague, Woerden, Oudewater, Vlaardingen’s Gravenzande, Schiedam, Vlaardingen, Rotterdam. South: Gorkum, Asperen, Heukelum, Arkel, Heusden

FIGURE 5

Interest rates on redeemable annuities 1514 (all villages)

There are several reasons to assume that the low level of integration in the North had much to do with the absense of large towns: the availability of money in large urban economies is likely to have been superior, and wealthy elites in large towns were more likely to invest their savings in financial markets. But it is also possible that this part of Holland was poorly integrated with the economy of the rest of the county.48 Direct evidence for the latter idea comes from the villagers of Petten, in the far north of Holland, who claimed in 1514 not to have sold annuities «because their remote location and poverty reduced their creditworthiness».49

In sum: participants in financial markets negotiated premiums on redeemable annuities ranging from 5 % to 10 %. However, most annuities by far were sold at interest rates around 6 % to 7 %. Interest rates were usually quite similar, in large and small towns and in the countryside. Villages in the North seem to have had most trouble gaining access to capital markets: here we encounter a wide range of premiums paid by villages. The low variation in interest rates seems to indicate that financial markets functioned quite well in the centre and South of Holland: they connected supply and demand in a way that prevented the emergence of «pockets» where premiums were either relatively high or low. The exceptance was the North of Holland, where interest rates show a much greater volatility, presumably due to a low level of urbanization and economic integration with the rest of Holland.

V

At the end of the late middle ages financial markets in Holland brought people looking to invest their savings in contact with public bodies looking for funding. They did so on a local, regional and interregional level. Towns could be particularly successful in attracting savings from foreigners: a considerable share of the public debt Leiden, Groningen and Nijmegen created was contracted with people from out of town, and often even from outside the province. In Holland only small differences in interest rates existed between large towns, small towns and villages: except for the north of Holland there is little evidence for the existence of «pockets» where interest rates were either very high or very low. For the rest financial markets thus appear to have been quite efficient in bringing together supply and demand.

To what degree there was already a certain degree of integration of financial markets is difficult to determine. The absence of pockets in the largest part of Holland might point in this direction, but on the other hand we are unaware of how quickly financial markets reacted to interest rates fluctuations elsewhere.50 Still, it may be useful to dwell a little upon the subject of market integration. First of all, it does not seem unreasonable to ascribe the small range of interest rates we encountered in Holland to the network of brokers towns used to create public debt. These provided towns with information on where to sell annuities abroad. It could well be that these networks helped to reallocate savings in a more-or-less efficient way and thus reduced price volatility. The credit networks of smaller towns and villages may have functioned in the same way, but probably more on a regional than interregional level.

The role polities’ demand played in reallocating savings in late-medieval societies may help to remind us of the importance of political economy in pre-industrial societies. The state often was the main force behind macro-economic phenomena, whereas private initiatives did not yet have a comparable impact.51 Yet, there also was a more intricate and complex relation between public debt and private enterprise, because in order to create interregional public debt, polities depended on community responsibility systems that were tied to trading networks. Interregional public debt was possible because towns made all inhabitants liable for default; this means that their creditors predominantly derived security from the possibilities they would have to apprehend a merchant from the polity they had lend to. Therefore supra-local public debt followed existing trading networks. As a result, financial markets could not exceed trading networks, and possibilities for expansion were limited.52 Or, to return to the towns and villages in the north of Holland: assuming these were indeed poorly integrated in the county’s economy, it is easy to see that this severely reduced their possibilities to attract foreign funding. Our study suggests alternatives existed to the mechanism David Stasavage described. Where demand for public debt was not met by the local investing public, authorities had to look for foreign investors. Using the community responsibility systems governments of less wealthy polities managed to tap into foreign savings. They thus used financial markets for what they ideally ought to do: to allow local governments looking for funding to exceed local supply.

1 Stephan R. Epstein: Freedom and growth. The rise of states and markets in Europe, 1300-1750, London / New York, Routledge, 2000. Cf. the decline in interest rates Stephen Broadberry, Sayantan Ghosal & Eugenio Proto: «Commercialisation, Factor Prices and Technological Progress in the Transition to Modern Economic Growth», Warwick economic research papers, 852 (2008); Gregory Clark: The Interest Rate in the Very Long Run: Institutions, Preferences and Modern Growth (working paper 2005); Ian Blanchard: «International Capital Markets and their Users, 1450-1750», in Maarten R. Prak (ed.): Early Modern Capitalism. Economic and Social Change in Europe, 1400-1800, London, Routledge, 2001, pp. 107-124; Sidney Homer & Richard Sylla: A history of interest rates, Hoboken, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2005 (4th edition).

2 Jan Luiten van Zanden: The long road to the Industrial Revolution. The European economy in a global perspective, 1000-1800, Leiden / Boston, Brill, 2009; I. Blanchard: «International Capital Markets»; Donald N. McCloskey & John Nash: «Corn at interest: the extent and cost of grain storage medieval England», American Economic Review, 74 (1984), pp. 174-187; Michael M. Postan: The medieval economy and society, London, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1972.

3 John Munro: The Monetary Origins of the «Price Revolution»: South German Silver Mining, Merchant-Banking, and Venetian Commerce, 1470-1540 (Working paper Department of Economics and Institute for Policy Analysis University of Toronto, 1999); Ian Blanchard: «English royal borrowing at Antwerp, 1544-1574», in Marc Boone & Walter Prevenier (eds.): Finances publiques et finances privées au bas moyen âge. Actes du colloque tenu à Gand les 5 et 6 mai 1995, Louvain / Apeldoorn, Garant, 1996, pp. 57-71; Hans-Peter Baum: «Annuities in late medieval Hanse towns», Business History Review, 59 (1985), pp. 24-48.

4 Douglass C. North & Barry R. Weingast: «Constitutions and commitment: the evolution of institutions governing public choice in seventeenth-century England», The Journal of Economic History, 49 (1989), pp. 803-832; Douglass C. North: Institutions, institutional change and economic performance, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1990, p. 69; Stephan R. Epstein: Freedom and growth, pp. 61-62. Clark, however, has suggested that the decline was due to changes in the «time preference» of people, who came to prefer saving over spending over time (G. Clark: The Interest Rate).

5 I. Blanchard: «International capital markets». Cf. monetary unions in the German Empire: Oliver Volckart & Lars Boerner: «…darumb als dann die Bequemikeit eyner einigenn Muntz sich manigfaltig erzeigen mocht…. Spätmittelalterliche Währungsunionen und ihre Folgen», Bankhistorisches Archiv. Zeitschrift für Bankegeschichte, 33 (2007), pp. 103-123.

6 David Stasavage: States of credit. Size, power and the development of European polities, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2011, p. 14.

7 Anthony Molho: «The state and public finance: a hypothesis based on the history of late medieval Florence», Journal of Modern History, 76 suppl. (1995), pp. 97-135; David Herlihy & Christiane Klapisch-Zuber: Les Toscans et leur familles, p. 251; William M. Bowsky: The finance of the commune of Siena 1287-1355, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1970, pp. 189-191, 199-200, 223-224.

8 Charles Tilly: «Entanglements of European cities and states», in Charles Tilly & Wim P. Blockmans (eds.): Cities and the rise of states in Europe, A. D. 1000 to 1800, Boulder, Westview Press, 1994, pp. 1-27, there 24.

9 How access to financial markets allowed polities in the province of Holland to organize themselves, has been described by James Tracy (James D. Tracy: A financial revolution in the Habsburg Netherlands. Renten and renteniers in the County of Holland 1515-1565, Berkeley / Los Angeles / London, University of California Press, 1985; idem: Holland under Habsburg rule 1506-1566. The formation of a body politic, Berkeley / Los Angeles / London, University of California Press, 1990.

10 Raymond van Uytven: «De macht van het geld: financiers voor Floris V», in Dick Edward Herman de Boer, Erich H. P. Cordfunke & Herbert Sarfatij (eds.): Wi Florens… De Hollandse graaf Floris V in de samenleving van de dertiende eeuw, Utrecht, Matrijs, 1996, pp. 212-223.

11 John H. Munro: «The medieval origins of the financial revolution: usury, rentes, and negotiability», International History Review, 25 (2003), pp. 505-562; James D. Tracy: «On the Dual Origins of Long-Term Urban Debt in Medieval Europe», in Marc Boone, Karel Davids & Paul Janssens (eds.): Urban Public Debts. Urban governments and the market for annuities in Western Europe (14th-18th centuries), Turnhout, Brepols, 2003, pp. 13-24.

12 Here, I will use the term «interest rate» to refer to the rate of return on annuities (purchase price/annuity). Of course, the people that contracted annuities in the late Middle Ages would have had another conception of this rate of return.

13 Cf. surveys: Charles P. Kindleberger: A financial history of Western Europe, 2nd edition, New York, Oxford Universty Press, 1993, pp. 37-56; Edmund B. Fryde & Matthew M. Fryde: «Public credit, with special reference to North-Western Europe», in Michael M. Postan, Edwin E. Rich & Edward Miller (eds.): The Cambridge Economic History of Europe. Volume III. Economic Organization and Policies in the Middle Ages, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1963, pp. 430-553.

14 J. H. Munro: «The medieval origins».

15 Jaco Zuijderduijn: Medieval Capital Markets: Markets for Renten, State Formation and Private Investment in Holland (1300-1550), Leiden / Boston, Brill, 2009, pp. 144-145, 252-258.

16 J. H. Munro: «The medieval origins», pp. 521-524.

17 Jules Lameere & Henri Simont (eds.): Receuil des anciennes ordonnances de la Belqique. Deuxième série. 1506-1700. Tome quatrième, Brussels, J. Goemaere, 1907, p. 235. Imperial charter of 4-10 1540 entitled «Eeuwig edict». This maximum of 12 % applied to loans contracted by merchants, and, probably, redeemable annuities. There is no evidence that the decree also applied to life annuities. For the rest of the late Middle Ages, there is little evidence of the imposition of maximum interest rates (J. Zuijderduijn: Medieval capital markets, pp. 243-244).

18 J. Zuijderduijn: Medieval capital markets, pp. 107-108.

19 Johannes Hermann Kernkamp (ed.): Vijftiende-eeuwse rentebrieven van Noordnederlandse steden, Groningen, Wolters, 1961, pp. 60-61; J. Zuijderduijn, Medieval capital markets, pp. 134-135.

20 Cf. other examples of representatives of towns travelling abroad to sell annuities: J. H. Kernkamp: Vijftiende-eeuwse rentebrieven, p. 61; Jacques Cornelis van Loenen: De rente-last van Haarlem, unpublished manuscript available at the Rijksarchief Kennemerland, pp. 6-8, 10-11.

21 J. Zuijderduijn: Medieval capital markets, pp. 112-113. Cf. other examples of towns making use of the service of brokers: ibidem, pp. 114-115; Lambertus M. VerLoren van Themaat et al. (eds.): Oude Dordtse lijfrenten. Stedelijke financiering in de vijftiende eeuw, Amsterdam, Verloren, 1983, pp. 55-56; J. C. Van Loenen: De rentelast van Haarlem, pp. 6-7.

22 J. H. Kernkamp: Vijftiende-eeuwse rentebrieven, pp. 60-61.

23 Ibidem, p. 61.

24 J. Zuijderduijn: Medieval capital markets, pp. 172-173.

25 Cf. further evidence of price making the varying interest rates Richter discovered in Hamburg and Bohmbach in Braunschweig (Klaus Richter: Untersuchungen zur hamburger Wirtschafts – und Sozialgeschichte um 1300 unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der städtischen Rentengeschäfte 1291-1330, Hamburg, H. Christians, 1971, p. 137; Jürgen Bohmbach: «Umfang und structur des Braunschweiger Rentenmarktes 1300-1350», Niedersächsisches Jahrbuch für Landesgeschichte, 41/42 (1969-1970), pp. 119-133, 131.

26 G. Clark: The Interest Rate, p. 5.

27 J. Zuijderduijn: Medieval capital markets, pp. 124-136.

28 See Avner Greif: «Institutions and impersonal exchange: from communal to individual responsibility», Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, 158 (2002), pp. 168-204; idem: Institutions and the path to the modern economy: lessons from medieval trade, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2006, pp. 309-313; Lars Boerner & Albrecht Ritschl: «Individual enforcement of collective liability in premodern Europe», Journal of institutional and theoretical economics, 158 (2002), pp. 205-213.

29 Piet Lourens & Jan Lucassen: Inwoneraantallen van Nederlandse steden, ca. 1300-1800, Amsterdam, NEHA, 1997, pp. 112-113.

30 For instance, in 1449 Leiden had to pay out 686 annuities.

31 Accounts for the «round» years of 1450 and 1550 were not preserved.

32 Jaco Zuijderduijn: «De laatmiddeleeuwse crisis van de overheidsfinanciën en de financiële revolutie in Holland», Bijdragen en mededelingen betreffende de geschiedenis der Nederlanden-Low Countries Historical Review, 125-4 (2010), pp. 3-24.

33 James D. Tracy: A financial revolution in the Habsburg Netherlands. Renten and renteniers in the province of Holland, 1515-1565, Berkeley / Los Angeles, University of California Press, 1985.

34 J. C. Van Loenen: De rentelast van Haarlem; Eef C. Dijkhof: Goudse renten, unpublished manuscript available at the Streekarchief Midden-Holland; J. Zuijderduijn: Medieval capital markets, pp. 177-181.

35 Petrus Johannes Blok: Rekeningen der stad Groningen uit de 16de eeuw, The Hague, S Gravenhage, M. Nijhoff, 1896, pp. 205-215, 345-353.

36 The following is based on Jaco Zuijderduijn: «Village-indebtedness in Holland (15th-16th centuries)», in Thijs Lambrecht & Phillipp R. Schofield (eds.): Credit and the Rural Economy in Europe, c. 1100-1850, Turnhout, Brepols, 2010, pp. 39-62, 40-41. The only part of Holland not investigated was the country of Voorne and Putten. Furthermore some villages under the jurisdiction of powerful noblemen, and therefore exempt of taxation, do not appear in the source (Robert Fruin (ed.): Informacie up den staet faculteyt ende gelegentheyt van de steden ende dorpen van Hollant ende Vrieslant om daernae te reguleren de nyeuwe schiltaele gedaen in den jaere MDXIV, Leiden, Boekdr. von A.W. Sijthoff, 1866, pp. VI, XXVIII).

37 R. Fruin: Informacie up den staet faculteyt, pp. IX-X.

38 Both Van der Woude and Noordegraaf have used the data the Informacie provides (Adrianus Maria van der Woude: Het Noorderkwartier. Een regionaal historisch onderzoek in de demografische en economische geschiedenis van westelijk Nederland van de late middeleeuwen tot het begin van de negentiende eeuw, Wageningen, Veenman & Zonen, 1972; Leo Noordegraaf: Hollands welvaren? Levensstandaard in Holland 1450-1650, Bergen, Octavo, 1985. Van Zanden used the informacie to come up with a national account of Holland for 1510-1514 (Jan Luiten van Zanden: «Taking the measure of the early modern economy: Historical national accounts for Holland in 1510-1514», European Review of Economic History, 6 (2002), pp. 131-163.

39 See for instance R. Fruin: Informacie up den staet faculteyt, pp. 149, 300. Hoppenbrouwers stressed the unreliability of the data on landed property in the informacie as well Peter C. M. Hoppenbrouwers, «Mapping an unexplored field. The Brenner debate and the case of Holland», in Peter C. M. Hoppenbrouwers & Jan Luiten van Zanden, Peasants into farmers? The transformation of rural economy and society in the Low Countries (middle ages-19th century) in the light of the Brenner debate, Tournhout, Brepols, 2001, pp. 41-66, p. 44.

40 Cf. R. Fruin: Informacie up den staet faculteyt, pp. 512-513; L. M. VerLoren van Themaat et al. (eds.): Oude Dordtse lijfrenten, pp. 123-127. At the end of the 15th century some towns made adjustments to annuities, to cope with arrears. This involved lowering the interest rate of annuities. The source does not take these adjustments into account; it offers an overview of the interest rates agreed upon when annuities were sold.

41 Noordwijk Archives, inv. nr. 291 (accounts of 1513 and 1516).

42 Jaco Zuijderduijn: «Het lichaam van het dorp. Publieke schuld op het Hollandse platteland rond 1500», Tijdschrift voor sociale en economische geschiedenis, 5 (2008), pp. 107-132, 118.

43 R. Fruin: Informacie up den staet faculteyt, p. 512.

44 Herman W. Dokkum & Eef C. Dijkhof: «Oude Dordtse lijfrenten», in Lambertus M. Ver-Loren van Themaat et al. (eds.): Oude Dordtse Lijfrenten. Stedelijke financiering in de vijftiende eeuw, Amsterdam, Verloren, 1983, pp. 37-90, 85-86.

45 «Seggen oock, dat, zoe zy niet gelooft en waeren meer renten up heurluyder dorp te vercoopen, zoe hebben zy upte huysen ende landen particulier gehaelt an losrenten 100 currente guldens tsjaers…» (R. Fruin: Informacie up den staet faculteyt, p. 234).

46 This pricing mechanism is best studied in: Timur Kuran & Jared Rubin: «The Financial Power of the Powerless: Socio-economic Status and Interest Rates under Partial Rule of Law», The Economic Journal, 128 (2016), pp. 758-796.

47 Jean Charles Naber: Een terugblik. Statistische bewerking van de resultaten van de informatie van 1514, Haarlem, Stichting Contactcentrum voor regionale en plaatselijke geschiedbeoefening in Noord- en Zuid-Holland, 1970 (reprint of edition 1885), pp. 36-37.

48 Cf. the importance of trade relations for the institutional framework of capital markets Lance Davis: «The capital markets and industrial concentration. The US and UK, a comparative study», The Economic History Review 2nd series, XIX (1966), pp. 255-272, 256.

49 R. Fruin: Informacie up den staet faculteyt, pp. 164-165.

50 Cf. Oliver Volckart & Nikolaus Wolf: «Estimating Financial Integration in the Middle Ages: What Can We Learn from a TAR Model?», The Journal of Economic History, 66 (2006), pp. 122-139.

51 Cf. Larry Neal: The rise of financial capitalism. International capital markets in the Age of Reason, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1990, p. 141.

52 This is also more or less why the bill of exchange did not become a major financial instrument. According to L. Neal: «this lending depended on the volume and intensity of commerce between any two cities. So it was limited to merchant bankers dealing in foreign trade, and to cities in close geographical proximity that were politically friendly» (Larry Neal: «How it all began: the monetary and financial architecture of Europe during the first global capital markets, 1648-1815», Financial History Review, 7 (2000), pp. 117-140, 118.

FIANZAS Y FIADORES EN EL SISTEMA FINANCIERO CASTELLANO A FINES DEL MEDIEVO: INSTITUCIONES GENERADORAS DE CONFIANZA*

David Carvajal de la Vega Universidad de Valladolid

A fines del Medievo la expansión de la economía, de los mercados, de los instrumentos y de las relaciones financieras era patente en buena parte del occidente europeo.1 Durante la Baja Edad Media, el progresivo desarrollo del mundo financiero impulsó un complejo entramado de vínculos que permitió integrar el capital en ámbitos como el comercio, la fiscalidad o la deuda pública y privada; haciendo posible el desarrollo y la consolidación de diversos «sistemas financieros», entendiendo estos como el universo conectado formado por instrumentos, instituciones y mercados, operando en un lugar y en un tiempo dados.2

61

Los centros italianos, franceses, flamencos, etc., asistieron como espectadores privilegiados de este proceso de auge financiero; si bien es cierto que a la hora de comprender el fenómeno de forma global, atendiendo a la mayor parte de los territorios de la Europa occidental, es fácil observar dinámicas y características que les hacen diferir entre sí. En palabras de Ch. Kindleberger, refiriéndose al estadio inicial de las finanzas occidentales en el que enmarcamos este trabajo, Europa era «una unidad que puede ser desagregada. Sus elementos son similares en términos generales, pero diferentes en los detalles»3. Por ello, sin obviar el contexto general, nuestra intención pasa por prestar atención al sistema financiero castellano y a ciertos aspectos del mismo que consideramos escasamente tratados.

Hoy conocemos, en líneas generales, las bases del sistema financiero castellano y de su desarrollo durante el Medievo gracias a diferentes aportaciones que han respondido más a preocupaciones puntuales que a un ejercicio de reflexión general.4 Con el ánimo de enriquecer este sustrato, y sabiendo de antemano que existen determinados ámbitos, como el de la fiscalidad, u operaciones, como el préstamo, que nos permiten esbozar la senda seguida por las finanzas castellanas, estimamos oportuno dedicar este trabajo, por un lado, a tratar la realidad castellana dentro del contexto europeo y peninsular y, por otro, al análisis de la fianza, una figura legal y económica poco considerada hasta ahora y que nos permite mostrar hasta qué punto las finanzas castellanas lograron un grado de madurez y complejidad notable. A fines del siglo XV, esta institución del derecho alcanzó plena vigencia dentro del entramado de relaciones que conformaban el sistema financiero castellano, dotándolas de la seguridad y de la confianza que requerían los partícipes.