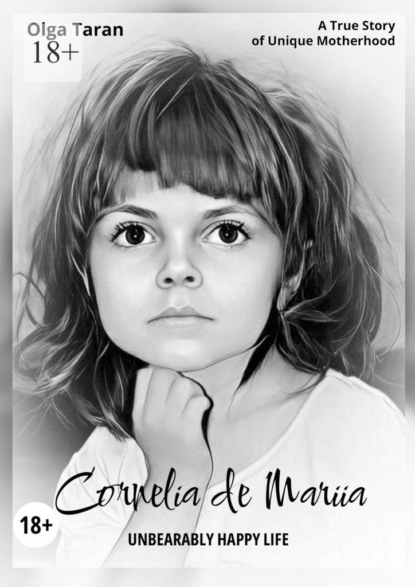

Cornelia de Mariia

- -

- 100%

- +

Translator Iuliia Zinkov

© Olga Taran, 2025

© Iuliia Zinkov, translation, 2025

ISBN 978-5-0068-4734-7

Created with Ridero smart publishing system

Recommended: Dear English-speaking reader,

As you dive into these pages, please remember that I come from a Russian background. My story, like any story, carries the weight of its original language, and while translation may alter some nuances, I hope the heart of my experiences still reaches you. Thank you for your patience and understanding as we bridge these languages and worlds together.

The same brown hue, the shape, the lashes,

Soul to soul, we walk our winding paths,

Taking flight like wounded birds.

In your eyes – an endless sorrow,

Despair, reproach, and pain…

They hold the cosmos…

Distance beyond distance…

A million voiceless sounds linger there…

In your eyes, a vast and boundless love,

The wisdom of past lives, and suffering.

There lie debts unpaid,

Depth…

Strength…

A calling…

Your eyes reflect mine:

Their gaze stirs quietly beneath the heart.

They don’t understand words…

But must they?

When the Universe lives in her gaze…

O.T. 2020

From the author

Cornelia de Lange.

Few doctors recognize that behind this beautiful name lies one of the most severe genetic syndromes in the world.

Marusya was born wanted, and everyone believed her to be healthy. But from five months on, problems began. Diagnoses poured in one after another: focal-resistant epilepsy, West syndrome, severe developmental delay. She was fading before our eyes. Only after four years of struggle, treatments, rehabilitation, trips to the best doctors, and endless attempts, was the primary diagnosis – the root cause – finally made: Cornelia de Lange syndrome, in an atypically severe form.

Did my world collapse? No. The world had fallen apart much earlier. By then, enough complications had accumulated to make it clear: there was no chance for a normal life. Moreover, the diagnosis brought me a sense of relief. I could finally fall asleep without the tormenting questions of why my child was the way she was. Knowing is always better than not knowing, no matter how painful it is.

What now? Now Marusya is eight, and our challenges remain unchanged. Marusya cannot walk independently, doesn’t understand speech, cannot chew, is not potty-trained, and so many other “cannots.” Every day, we continue to suffer from three types of epilepsy, which we cannot control due to the complex genetic nature. Marusya finds herself in intensive care more frequently now, each time slipping further into regression. And our prognosis, as doctors would say, is quite unfavorable. We have palliative care status – in simpler terms, Marusya is a hospice child. But! She can smile. And she is incredibly beautiful. Each day lived with a smile is already a great joy.

And how am I? Over these years, I have gone through all the stages of grief: from despair and thoughts of leaving life behind to complete acceptance. I have a law degree with honors and spent several years working in the field. December 3rd still brings congratulations for Lawyer’s Day. But now, I pay attention to this date for an entirely different reason.

Did I know that December 3rd is International Day of Persons with Disabilities? No.

Had I ever been interested in this topic? No.

What did I do if I happened to see a person with a disability on the street? I quickened my pace and looked away, just like most of us.

It’s all somewhere far away.

It happens to someone else, never to you.

And surely, these people bear some responsibility for their circumstances.

It’s easier for us to think this way.

So now, when I see an indifferent or fearful reaction to my child, I immediately want to lash out, but in a second, I remember myself – the person for whom December 3rd was only Lawyer’s Day.

I write a small blog where I honestly share our unique life.

Do I want pity and support? No. I’ve long since been the one giving support to others.

I hold my head high.

I don’t show anyone, not even myself, the pain that fills my entire being.

I resist, hoping for better changes.

I hope things won’t get worse.

I grow tired and sometimes simply don’t want to exist.

And at the same time, I am terribly afraid that one day, it will all come to an end.

I keep loving my eternal child with my weary heart, and I just want people to know of my daughter’s quiet existence and to see the magic in her eyes.

I have no goal of impressing you with artistic language. I stay true to myself and continue to write in the very style that many of you have come to love. Even less do I aim to inspire you to great deeds, to motivate you, or to show you “the right way.”

I don’t know the right way. I write it as it is. And as it was for me.

Our honest story…

Part 1. Life “Before”

I was sitting on the operating table in the maternity hospital, head slightly bowed to my chest, back arched. The anesthesiologist was administering a local spinal anesthetic. This was my second C-section; the sensations were familiar. I trembled slightly. My hands and feet shook, perhaps from fear, from the cold, or from memories. After all, two years ago, I had sat in this exact same position on this very table, only then, it wasn’t just nervousness – I was consumed by terror and panic.

My first delivery was an emergency. Everything happened unexpectedly for everyone involved. It’s a miracle we managed to avoid catastrophic consequences. My eldest girl wasn’t breathing when they delivered her. Triple nuchal cord entanglement. It seemed improbable, especially in the late stages of pregnancy, just days before delivery. But everything improbable can still happen. This would become even clearer to me in a couple of years.

This time, everything was different. Everything went according to plan. The C-section was scheduled at 38 weeks. Given the polyhydramnios, the large belly, and the scar on my uterus, the doctors decided not to wait. The baby was ready. Everything was exactly as it had been two years ago, but without the rush.

They delivered Masha. She let out a newborn cry, more like the groan of an adult.

“Who do we have here, born so serious?” the doctors laughed.

Yes, we couldn’t have imagined then who had been born to us or how serious she truly was.

They brought Masha to me, even placing her on my chest. A tiny, wrinkled face, clouded eyes, dark hair on her little body. From the very first look, it was clear – the youngest girl took after me. I felt wonderful. None of the stress or uncertainty of my first delivery. As they wheeled me from the operating room to the intensive care unit, I enjoyed my sense of calm, knowing that soon they would bring Marusya to me.

Why did I start from the moment of her birth? Because that’s where I get the most questions: “How did the birth go?” “How was the pregnancy?” “Did you have the screenings and tests done?”

Such questions make me smile now. I understand what lies behind them. A quiet kind of judgment. People need a reason for what’s happened because the idea that there might not be one is unbearable. Surely, they think, the woman didn’t get all the right tests, wasn’t careful about her health, maybe even allowed herself some alcohol.

How else could it be? If it’s not like that, it would shatter any sense of universal justice. Allowing the thought that a tragedy could enter your life without cause is terrifying. People want a logical explanation, a reassurance – “This won’t happen to me because I won’t make those mistakes!”

For most, the belief in a causal link between a woman’s actions or inaction and the birth of a sick child is deeply ingrained. “It’s her fault.” This viewpoint is quite common in our society. Surely, they assume, she drank and smoked. Surely, the woman whose husband nearly beats her to death must have done something wrong. We find it comforting to think this way. What lies behind it? Indifference? Arrogance? Knowledge? No. Behind it all is a great fear. A fear of losing control. A horrifying realization – “If this could happen without fault, it could happen to me.” And that’s a thought no one wants to let into their minds.

My pregnancy and delivery were routine. I had all the screenings, took all the tests, gave birth on time and without complications. But my answer rarely satisfies such listeners. They quietly slip away, and I’m sure they still leave convinced – something here just doesn’t add up.

_________

THE ICU (Intensive Care Unit)

The ICU (Intensive Care Unit) was already familiar to me. Nothing had changed here since my first delivery. They transferred me to a bed and gave me some water. Next to me lay a young woman, apparently from the previous night. She looked fairly energetic, sitting up on her own and even moving around a bit. She was visibly upset about not being able to give birth naturally and having to undergo a C-section.

I remembered Sasha, my eldest daughter. No, I didn’t have those pangs of guilt. Childbirth is a lottery. You never know how it will go. You have to be as prepared as possible for anything. But sometimes, after reading online articles about the importance of natural childbirth, about how terrible it is when a child doesn’t go through the natural birth canal, and about the exaggerated consequences of a C-section on a child’s development, women start blaming themselves. For what? For drawing the short straw?

We follow all sorts of imposed standards: give birth naturally, breastfeed exclusively, marry once and forever. Does this plan work out? In most cases, no. And we feel disappointed, cultivating a sense of endless guilt in our hearts. For what? For not doing things “the right way.” But who said there is a “right way”? It doesn’t even matter who or when this idea originated. We carry these beliefs as unquestionable truths. And so, my neighbor was deeply upset, unaware of what could have happened to her child if she had continued trying to deliver naturally. She knew it was for the best, but she still took it as a personal failure. We get disheartened, not realizing how lucky we are.

I was starting to feel better. From experience, I already knew that it’s best to start moving as soon as possible to recover faster. But this time, it was harder than the first. Again, I felt pain around my heart, shoulders, and arms. This muscle pain was a side effect of the anesthesia, and it had set in unusually early this time. The nurse monitored my condition, occasionally performing some procedures around my lower abdomen and below, but I wasn’t bothered by it.

What did bother me was the visit from the neonatologist. A tall woman with sad eyes looked at me with a kind of disdain.

“Did you know you have blood type O and a negative Rh factor?” she asked, without lifting her eyes from my chart.

“Of course.”

“And who even allowed you to give birth?” she then lifted her head, looking at me with a sneering smirk.

I was speechless. Seriously? I’m lying in the ICU after giving birth to my second child. I have two wonderful daughters, and this stranger of questionable demeanor, whom I’m seeing for the first time, asks me such a question?! I’d heard horror stories about this type of doctor – hostile psychopaths with medical degrees – but this was my first time facing one. I now look back on all those cynical, bitter women with a smile, but at the time, I was thrown off.

We’re unprepared when people come at us “full force,” and we don’t know how to defend our boundaries. We always seem to be apologizing, especially in interactions with doctors. This time, too, I was apparently supposed to apologize for my negative Rh factor and my reckless decision to have children without the approval of this great woman.

“To hell with you!” I thought, and that’s exactly what I would say now. But back then, the polite, straight-A student in me wouldn’t allow it, so I said something else instead:

“And what’s the problem?”

My eldest daughter was born with a negative Rh factor, so there were no issues, aside from a touch of jaundice due to blood type.

The question of mother-child blood compatibility is actually quite serious. It worried me throughout both pregnancies and was something I constantly researched and monitored.

When the mother has a negative Rh factor and the father a positive one, there’s a risk of Rh incompatibility during pregnancy. In everyday life, Rh factor isn’t usually significant, but in pregnancy, it’s essential. Scientifically speaking, the body contains blood cells – erythrocytes. On their surface, some people have a specific protein called the Rh factor. People with this protein are Rh-positive, and those without it are Rh-negative. Over 85% of the world’s population is Rh-positive.

Now, if a woman is Rh-negative and the fetus is Rh-positive, Rh incompatibility can develop. The child’s blood triggers the mother’s body to create antibodies, which then attack the “foreign” elements – in this case, the fetus’s blood cells. This reaction can lead to hemolytic disease in the newborn, as the healthy erythrocytes of the child are destroyed, producing bilirubin as a byproduct. High levels of bilirubin indicate that the child’s liver is struggling to produce enough new erythrocytes. In some cases, this can lead to severe complications or even death.

If the child also has a negative Rh factor, no conflict occurs. Sasha was born with a negative Rh factor, as was Masha, as the stern neonatologist informed me. This was certainly a relief. But it wasn’t quite that simple. I couldn’t forget that I have blood type O, which often causes blood-type incompatibility (Masha was born with type B). Typically, blood-type incompatibility is much milder than Rh incompatibility, so this type of conflict is less dangerous. Babies who experience it often have jaundice, which usually resolves on its own over time.

All this information was known to me and my doctors, so we were prepared for the possibility of jaundice if Masha wasn’t born with type O like me. This kind of statement – that I should have been forbidden to give birth – was bewildering. Such a comment could only come from an unqualified person, or more likely, it was about something else entirely!

“Your child’s bilirubin levels have risen. Jaundice began within the first day,” the doctor told me, as if I were a slow student.

I was prepared for this. We’d been through it with my eldest daughter. This woman evoked nothing but disgust in me, and I had no desire to continue the conversation – nor did she. Muttering something to herself, the doctor left.

In the evening, they transferred me to a regular room. The other mothers had their babies brought to them. I was the exception. Masha’s bilirubin continued to rise, and she was under the “lamp” – a phototherapy light used to treat newborn jaundice. The lamp’s secret lies in the blue ultraviolet rays it shines on the baby’s skin. Ultraviolet breaks down the bilirubin, turning it into an isomer that’s naturally expelled from the body. This reduces the excess bilirubin in the blood to safe levels.

I was allowed to visit Masha in the NICU (Neonatal Intensive Care Unit). It was close to my room, so I could go there often. Masha lay in a special incubator, a little cap pulled down over her eyes. The smallest diaper looked like a huge sack on her tiny body, as did the little socks on her miniature feet.

The NICU nurses, like the head neonatologist, were extremely curt and even aggressive. How could people working with newborns, people welcoming new life, be like this? I couldn’t wrap my head around it.

As time passed and I searched for answers to the severity of her issues, I replayed those days in my mind hundreds of times, especially Masha’s stay in the NICU. I couldn’t shake the feeling that the doctors in that department were involved – maybe even responsible – for the complications that developed. Negligence, a fall, a wrong injection. Their constantly irritated manner when speaking with me only fueled these speculations.

I received all updates on my child not from them but from the surgeon. And the day it all began, she was the one who came to me. Calm as always, she reported:

“Your child has a heart murmur. There is suspicion of a defect.”

This was the first shock. She continued to explain things at length, though I can’t recall her exact words. All I understood was that the elevated bilirubin was no longer their primary concern; now it was the “uncertainty” surrounding her heart.

A heart murmur. I informed my husband, then searched the internet. It’s amazing and terrifying at the same time that we have the internet. You can find everything you need – and everything you don’t. In any unfamiliar situation, the first thing we do, the first thing we do when we hear unfamiliar words, is, of course, to type them into the search bar. The real task is to sift through the information. And this is where things get complicated. First, you read the most horrifying possible outcomes, sending yourself into a panic. Then, you read miraculous recovery stories, convincing yourself it’s not serious at all (misdiagnosis, it’ll pass on its own, this happens often), and so on in a vicious cycle.

And yet, I’m grateful for the internet: it’s given me far more than all the doctors I’ve ever encountered put together. It gave me more than information! It gave me people and their experiences! Their real experiences of special-needs parenting, with all the fears, mistakes, victories, and disappointments. Special chats, special groups – these are what keep you afloat, keeping you from drowning even when you feel like you’re on the brink.

What exactly is a “heart murmur”? The human heart has four chambers – two atria and two ventricles. Between them are valves that constantly open and close. The heart fills and empties in sequence as it contracts, with moments of silence between beats. Sometimes, however, abnormal sounds – murmurs – can be heard during these silences. These murmurs are often linked to anatomical abnormalities in the heart’s structure. Some can lead to disability, while others are completely harmless. The key is to determine the cause of the murmur.

My head was spinning. Heart murmur. What could be the cause? With one hand, I scrolled through my phone, while with the other, I pumped milk from my swollen breasts. I wasn’t allowed to breastfeed. Due to medical guidelines related to blood-type incompatibility, breastfeeding had to be temporarily suspended. In this situation, I needed to pump to maintain lactation. This was easy enough – I had plenty of milk. So much, in fact, that as I sat on the bed in the narrow cubicle, milk spurted from my nipples directly onto the wall. This sight was quite amusing and entertained my cubicle neighbor as well as the doctors who came into the room. For me, though, it was anything but funny. I watched with envy as my neighbors serenely nursed their babies. Why, once again, was the happiness of welcoming a new life starting with stress?

_________

The bilirubin levels weren’t decreasing despite the lamp treatment. The cause of the heart murmur remained unclear, so it was decided we’d be transferred to the neonatal department at the city hospital. I was disheartened. I had clung to the hope that, like with Sasha, the bilirubin levels would gradually go down, and we’d be discharged. But the additional heart issues extinguished that hope entirely.

All my neighbors were discharged, but there was no joyful discharge for me. Another hospital visit. This time, the department was far more modern than the maternity hospital. Fresh renovations, rooms for two mothers with their children, a dining area, a decent shower. Overall, everything looked quite civilized. They placed Masha under the lamp immediately; it was set up in the room, right next to my bed. A doctor arrived. She was very polite and professional, explaining how to use the lamp, position the baby in the incubator, and which tests would be done in the coming days. Compared to the doctors at the maternity hospital, this was a whole new level. It gave me a bit of confidence.

Masha lay in the incubator like a little sunflower. Her tiny yellow face looked even smaller now. She had lost more weight than was recommended and was down to just 2,600 grams. It felt like a disaster. Masha was born with a low weight—2,900 grams – even though I was sure, judging by my belly, that she’d be bigger than her older sister. Why was her weight so low? They assured me that it wasn’t a problem, and she was within the normal range. But now, 2,600! I started to panic. I studied her tiny body and couldn’t wait until I’d be allowed to breastfeed. I needed to get my baby fed!

A nurse came into the room.

“I’m taking the baby for tests and a heart ultrasound,” she informed me. My heart pounded. When would this end? I just wanted some certainty, at least about her heart. What was going on? What if it’s a defect that requires surgery? What if it’s something she can’t live with for long? I tried to shake off these thoughts, distracting myself with the routine of hospital life.

Between the two rooms were large glass windows, so I could see everything happening next door. There were a few babies in there, and doctors were constantly coming in to examine, feed, and care for them, but their mothers weren’t there. Strange. Whose children were they?

They brought Masha back, unwrapped her, and placed her under the lamp. She rarely cried, always calm, almost sluggish.

“Wait for the doctor. She’ll come and explain everything.”

Waiting again! The hardest part is waiting, trying to rein in your wild imagination. I heard the clinking of glass bottles. Every three hours, baby formula in warm bottles was brought to the rooms. Masha would take the bottle, but she ate with little appetite, never finishing the recommended amount. This upset me deeply. She was already so small.

The doctor arrived, asking how her feeding was going. She was very calm. I watched her closely, trying to understand if there was something she was hesitant to tell me gently.

“Bilirubin is still high; we’ll continue with the lamp treatment. If levels keep rising, a blood transfusion might be needed. But I hope it won’t come to that,” she informed me. By then, I’d come to terms with the bilirubin issue. My concern lay elsewhere.

“And what about her heart?”

“Oh, yes, her heart! It’s just some extra chordae. Nothing serious,” the doctor said, almost in passing.

And that’s it?! Just like that? Days of panic, sleepless nights, fear, the sorrowful looks from the maternity doctors, talks of a heart defect, and it’s just “nothing serious.” And it only took a few minutes of ultrasound to find that out?

Extra chordae. They form in the fetal heart around the fifth week of pregnancy. Only specific types (hemodynamically significant chordae) pose a risk by affecting blood flow speed and possibly causing tachycardia or arrhythmia in infants. In most cases, extra chordae are harmless, discovered by chance, and require no treatment. That was our case as well. This common micro-pathology appears in 22% of children – or at least among those examined. Do all mothers whose babies the maternity hospital doctors find murmurs in receive the same somber warning of a potential heart defect? Without even confirming it?

How strange this all is! Yes, I was still at the very start of my long journey. I hadn’t yet realized that most doctors keep all their knowledge to themselves, as if afraid to spill it, giving you only scraps of information. Want to know more? Want to delve deeper, look up statistics, find examples, prognosis, course, complications? Be prepared to research it yourself. But you don’t realize this at first. Initially, you trust.