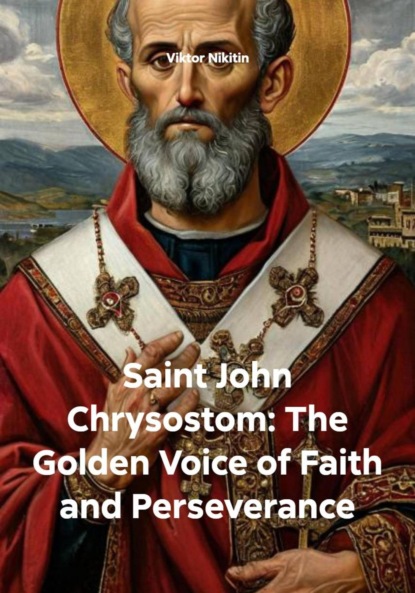

Saint John Chrysostom: The Golden Voice of Faith and Perseverance

- -

- 100%

- +

Chapter I: From His Birth to His Appointment to the Office of Reader, A.D. 345 or A.D. 347 to A.D. 370

In the holy city of Antioch, renowned for its grandeur and learned schools, there was born unto a noble and devout Christian family a child blessed from heaven, who was named John. His father, Secundus, a soldier of notable rank in the imperial army, and his mother, Anthusa, a woman of great piety and steadfast faith, bestowed upon him not only the privileges of noble birth but also the richness of Christian upbringing. Yet the Lord, in His inscrutable providence, saw fit that the father should be taken from the child’s life in his earliest years, leaving young John under the tender and watchful care of his mother.

Anthusa, a woman adorned with patience and love, devoted herself fully to the raising of her son in the fear of God. From the first days of his infancy, she infused into his soul the knowledge of the Scriptures, teaching him to know and love the Almighty Lord, who made heaven and earth. The boy was frail in body, his constitution weak and delicate, and thus his days were spent mostly in quiet reflection and study rather than the noisy games of other children. Yet in this seeming frailty was concealed a spirit of rare strength, for John’s heart burned with the desire for holiness, and his mind thirsted for divine wisdom.

From a young age, John was drawn to the sacred writings. The Holy Scriptures became his closest companions; he treasured them above all earthly delights. He learned to read the sacred texts with an earnest heart, meditating upon the words of the prophets, the psalms of David, and the teachings of the apostles. His memory was sharp, his understanding keen, and his soul sought to emulate the saints and martyrs whose lives he devoured in countless volumes.

Antioch, a city bustling with merchants, philosophers, and scholars, was also a place where worldly distractions abounded. Yet John’s heart remained untouched by the temptations that surrounded him. His mother ensured that he was trained not only in piety but in the arts of rhetoric and philosophy, disciplines held in great esteem by the learned of the day. Thus he entered the famous schools of Antioch, where he studied the Greek language and the art of eloquence, laying the foundation for the powerful voice he would one day raise in defense of the faith.

Though versed in rhetoric, John was unlike many of his contemporaries who sought fame and applause. His was a voice destined to proclaim the eternal truths of God, and thus he sought not vain glory but the purification of his soul and the salvation of others. The wisdom of the philosophers could never satisfy the hunger of his spirit; only the living God could fill the void within.

In his youth, John encountered many teachers, but none inspired him more than the holy bishop Diodorus, who nurtured his spiritual growth and encouraged him to seek the monastic life. John’s desire for solitude and prayer deepened, even as he fulfilled his worldly duties as a student and a young man of society. The seeds of asceticism were planted early in his soul, preparing him for the years of fasting, prayer, and labor that lay ahead.

Before long, the Church took note of John’s virtues and gifts. Recognizing his purity of heart and his exceptional talent in reading and proclaiming the Scriptures, the clergy appointed him to the office of reader, a sacred ministry by which the Word of God was proclaimed to the faithful during the divine services. This was a great honor, but John accepted it not with pride but with humility and trembling. He understood that he had been entrusted with a sacred duty, one that required both knowledge and holiness.

As reader, John’s voice became known in the churches of Antioch. His intonations brought life to the ancient words of the prophets and apostles, stirring the hearts of the people. Many were drawn by the power of his reading, sensing in him a soul aflame with divine love. The young John labored zealously in this office, seeking always to grow in virtue and understanding, preparing for the greater responsibilities that the Lord would soon lay upon him.

Throughout this time, John lived modestly, rejecting the excesses of wealth and status. His chamber was simple, his garments plain, and his meals sparse. He practiced prayer and fasting even as he fulfilled his duties, desiring above all to be conformed to the image of Christ, the Good Shepherd, who laid down His life for His flock.

Thus passed the early years of John Chrysostom, from his birth into a noble Christian family, through his education in the schools of Antioch, to his appointment as reader. His life was marked by humility, learning, and a growing passion for holiness. The foundation of his saintly life was laid in these years, a foundation that would support the mighty edifice of his future ministry as preacher, ascetic, and bishop.

God, who had chosen him from the womb, was preparing John for the great trials and glories that awaited him. The path was not yet clear, but the light of divine grace shone steadily upon him, guiding his footsteps toward the fulfillment of his sacred vocation. The Lord’s hand was upon John, shaping him to be a voice crying in the wilderness, a beacon of truth and sanctity for the Church and the world.

Chapter II: Commencement of Ascetic Life—Study Under Diodorus—Formation of an Ascetic Brotherhood—The Letters to Theodore. A.D. 370

Having been appointed reader and having already begun to proclaim the holy Scriptures, John Chrysostom found within his heart a growing desire to renounce the fleeting vanities of this world and to consecrate himself entirely to God. From his earliest youth, the seeds of asceticism had been planted in his soul, watered by prayer and meditation, and now the time had come for those seeds to bear fruit. It was around the year 370 that John sought the guidance of Bishop Diodorus of Tarsus, a man renowned for his strict ascetic discipline and profound knowledge of Holy Scripture.

Under the tutelage of Diodorus, John entered a deeper life of prayer, fasting, and study. The bishop, recognizing the fervor and sincerity of the young man, took him into his confidence and instructed him in the ways of the desert fathers—men who had forsaken the world to seek God in solitude and contemplation. Diodorus taught John that true wisdom comes not only from study but from the purification of the soul and the mortification of the flesh. To be a true servant of Christ, one must deny oneself and take up the cross daily.

In this spirit, John embraced the ascetic life with zeal. He withdrew from the distractions of the city and formed, with several companions of like mind, a brotherhood devoted to the strict observance of monastic discipline. These men lived together in poverty, chastity, and obedience, dedicating their days to prayer, manual labor, and the study of Scripture. They sought to imitate the example of the apostles and the desert monks, following the counsel of the Gospel to sell all and give to the poor, to pray without ceasing, and to live in unity and charity.

This brotherhood became a haven of holiness in the midst of a world growing increasingly lax in faith. Their lives were marked by frequent fasting, often eating no more than once a day, sometimes less, and rising in the dead of night to pray before the Lord. They wore simple garments and endured hardships without complaint, rejoicing that their sufferings united them to the sufferings of Christ.

It was during this formative period that John began to correspond with Theodore, a fellow ascetic and spiritual friend, who was himself engaged in the struggles of the monastic life. Their letters, filled with pastoral wisdom and brotherly exhortation, reveal the depths of John’s spiritual insight and his tender care for those seeking to live virtuously. In these letters, John encourages Theodore to persevere through temptation and discouragement, reminding him that the path of holiness is narrow and fraught with trials, but that the reward is eternal life.

John’s letters to Theodore also speak of the dangers of pride and self-deception, common snares for those who undertake the ascetic life. He warns against false humility and hypocrisy, urging honesty and sincere repentance. He exhorts his friend to guard the heart zealously, for it is the source of both good and evil. These letters stand as a testament to John’s growing maturity as a spiritual father, one who would later guide countless souls with the same care and love.

In addition to his letters, John composed treatises defending the monastic vocation against those who criticized it as excessive or unnecessary. He argued that asceticism was not an escape from the world but rather its sanctification, a way to bring the light of Christ into every corner of human life. Through self-denial and prayer, the monk becomes a living witness to the kingdom of God, a light shining in darkness.

Despite his withdrawal from worldly honors, John’s reputation as a holy man and gifted preacher began to spread. The faithful came to him for counsel and blessing, drawn by the fragrance of his virtue and the power of his words. Yet John remained humble, seeing himself as a servant of all rather than a master, and ever seeking to conform his will to God’s.

Thus in these years, John Chrysostom was shaped by the rigors of asceticism, the wisdom of his spiritual father Diodorus, and the fellowship of his brotherhood. His soul was purified like gold in the fire, preparing him for the great ministry that awaited him. The Lord was refining His chosen vessel, that he might bear the weight of the episcopal office with courage and holiness.

The ascetic life was not an end in itself for John, but a means to greater service. His prayers and labors were always offered for the salvation of the Church and the world. And so, from the quiet cells of the monastery, the voice of John Chrysostom began to rise—a voice destined to thunder forth from the pulpits of Antioch and Constantinople, calling all to repentance, faith, and love.

Chapter III: Chrysostom Evades Forcible Ordination to a Bishopric—The Treatise “On the Priesthood.” A.D. 370, 371

The Lord, in His divine wisdom, often prepares His servants through trials and unexpected challenges, and such was the case with John Chrysostom. As his reputation for holiness and learning grew, many in the Church saw in him the qualities befitting a bishop. Yet John himself was reluctant to accept such an office. The burden of the episcopate was heavy, the world often unkind to its servants of God, and John desired above all to live a humble life of prayer and asceticism.

Despite his protests and efforts to avoid the honor, there came a time when those in authority sought to thrust the episcopal mantle upon him. It is said that certain factions endeavored to compel him by force, fearing that his saintly presence might slip away from them if left free. John fled from their grasp, seeking refuge in the solitude of the wilderness, preferring exile and hardship rather than the worldly honors and the responsibilities that he foresaw would weigh upon his soul.

In this flight, he wandered among the mountains and deserts, seeking to hide from the eyes of men and to commune only with God. His heart was torn between the desire for solitude and the call to serve the Church, a tension that would mark much of his life. Yet even in retreat, his mind remained active, pondering the duties and sacredness of the priestly office.

It was in this time of contemplation that John composed his monumental treatise, “On the Priesthood.” This work stands as a profound meditation on the nature and responsibilities of the priestly office, revealing the depth of his understanding and the sincerity of his vocation. He wrote not as one eager for power, but as a servant humbled by the weight of the task.

In this treatise, John speaks of the priest as a mediator between God and men, a shepherd called to lay down his life for the sheep. He portrays the priesthood as a sacred trust, demanding purity of heart, humility, and zeal for the salvation of souls. The priest must imitate Christ, the Great High Priest, bearing both the joys and sufferings of the flock with love and patience.

John warns against pride and ambition, which so often corrupt those who seek ecclesiastical power. He reminds priests that their true honor lies not in worldly esteem but in the holiness of their lives and the efficacy of their prayers and sacrifices. The priesthood is a yoke that binds the soul to Christ, and only those who bear it with humility can find true freedom.

The treatise also reveals John’s profound pastoral concern. He exhorts priests to be vigilant shepherds, not greedy hirelings, ready to defend the faithful from error and sin, yet always ready to forgive and restore with gentleness. The salvation of souls is their chief aim, and all else is secondary.

As John wrote, his spirit burned with love for the Church and a deep sense of responsibility. Though he fled the episcopal office, he did so not out of cowardice but out of reverence for the sacredness of the task. He knew that to be a true bishop required a heart wholly given to God, and he sought to prepare himself for such a calling by prayer and study.

Eventually, the hand of God would lead John from the wilderness of retreat back into the midst of the Church’s struggles and labors. But in these years of solitude and reflection, he fashioned a spiritual armor that would sustain him through the storms to come. The treatise “On the Priesthood” remains a timeless guide and testimony to the holiness and gravity of the sacred ministry.

Through it all, John’s humility shone forth as a beacon. Though sought after by men for office, he placed the glory of God and the salvation of souls above all earthly honors. The Lord saw in him a heart ready to be tested and refined, a voice that would speak boldly for the truth.

Thus, even as he evaded the forcible ordination sought by others, John Chrysostom’s soul was being shaped for the episcopal calling that awaited him—a calling he would one day embrace with courage, wisdom, and unshakable faith.

Chapter IV: Narrow Escape from Persecution—His Entrance into a Monastery—The Monasticism of the East, A.D. 372

In the years following his retreat into the wilderness, John Chrysostom found himself drawn more deeply into the monastic life, that sacred vocation which had taken root in the East and flourished among the deserts and hills of Syria and Palestine. The ascetic movement was flourishing, a shining light amid the darkness of the age, and John sought to join its ranks fully, embracing the rigors and sanctity of the monastic calling.

Yet even in this pursuit, the world and its trials were not far behind. For those who sought to live for God in simplicity and humility were often met with opposition from those who feared their influence or misunderstood their purpose. John narrowly escaped persecution by certain authorities who, perhaps threatened by his growing reputation and unyielding spirit, sought to silence him.

Fleeing from such dangers, John found refuge in a monastery, a place set apart from the clamor of the city and the intrigues of the world. Here, among the brothers who had dedicated themselves wholly to prayer, fasting, and manual labor, John found the spiritual nourishment he so desperately sought. The monastery became his sanctuary, a place where the soul could be purified and the heart united to God.

The monasticism of the East, unlike the later Western monasticism, was characterized by an intense spirit of solitude and rigorous discipline. The monks lived in communities but also sought solitude in the deserts, caves, and wilderness, wrestling with demons and striving for purity of heart. Their lives were marked by asceticism of the body and soul, a ceaseless striving toward the heavenly kingdom.

John immersed himself in this holy environment, learning from the elder monks the disciplines of silence, fasting, and prayer. He rose before dawn to pray in the dark, chanting the Psalms with a voice that soared like an incense offering to the heavens. His days were filled with labor in the fields or in the scriptorium, copying sacred texts, while his nights were given to vigils and contemplation.

The monastic rule, though unwritten, was strict. The monks shared all things in common, denied themselves worldly comforts, and embraced poverty, chastity, and obedience as the foundation of their life. This radical renunciation was not for the sake of self-mortification alone but as a way to free the soul from earthly attachments and to open the heart fully to divine grace.

In this crucible of sanctity, John’s spirit was tested and strengthened. The tempests of temptation assailed him—the lure of pride, the weariness of fasting, the loneliness of exile—but he overcame them through humility and trust in God. The monks witnessed his holiness and sought his counsel, recognizing in him a soul aflame with divine love.

This period of monastic formation was crucial for John. It not only purified his soul but deepened his understanding of the spiritual warfare that every Christian must wage. The desert fathers, whose writings he studied and whose example he followed, taught him that the true monk is a soldier of Christ, armed with prayer, fasting, and the Word of God.

Though John’s monastic life was austere, it was not devoid of charity. He ministered to the poor and the sick, offering comfort and hope. His love extended beyond the cloister walls, for he saw in every human being the image of God, worthy of respect and care.

The monastery also became a place of study, where John deepened his knowledge of Scripture and the Fathers. His mind, already sharp from earlier schooling, now drank deeply from the wellsprings of Christian wisdom. The spiritual insights gained during these years would later shine forth in his sermons and writings, illuminating the Church with the light of divine truth.

Thus, through trial and grace, John Chrysostom was molded into a true monastic father, a man whose life was hidden with Christ in God. His narrow escape from persecution and his subsequent entrance into the monastery marked a new chapter in his pilgrimage, one that would prepare him for the immense responsibilities that awaited him in the service of the Church.

The Lord was shaping in John a vessel worthy of His use, a beacon of holiness and courage for generations to come. In the quiet cells of the monastery, away from the noise of the world, the saint’s soul was being forged in the fire of divine love.

Chapter V: Works Produced During His Monastic Life—The Letters to Demetrius and Stelechius—Treatises Addressed to the Opponents of Monasticism—Letter to Stagirius

In the serene solitude of the monastery, amidst ceaseless prayer and humble labor, John Chrysostom’s mind and spirit flourished. It was a time not only of personal sanctification but also of fruitful labor for the Church through his writings and correspondence. Though removed from the bustle of the city, John’s heart was deeply engaged in the struggles of the Christian faithful and the challenges facing the monastic vocation itself.

Among the fruits of this period are the letters he addressed to notable figures such as Demetrius and Stelechius, men devoted to the ascetic life but grappling with the trials and temptations that so often accompany the path of holiness. In these letters, John offers encouragement and practical advice, exhorting them to steadfastness, humility, and love. His words reveal a tender spiritual father, deeply concerned for the welfare of his spiritual children and eager to strengthen their resolve.

John’s letters often touch upon the difficulties of monastic life: the battle against pride and despair, the struggle to maintain purity of heart, and the importance of obedience to the monastic rule. He reminds his correspondents that the ascetic life is a journey of continual repentance and that even the greatest saints are but sinners saved by grace. These exhortations reflect John’s profound understanding of human weakness and the necessity of divine aid.

During this time, John also engaged in theological and pastoral writing aimed at defending the monastic vocation against its critics. Many in the Church, both clergy and laity, viewed monasticism with suspicion or disdain, seeing it as an unnecessary withdrawal from the duties of the world. Some accused monks of pride or hypocrisy, while others questioned the value of such rigorous self-denial.

In response, John penned treatises that articulated the spiritual necessity and benefits of monasticism. He argued that the monastic life is not an escape from the world but a means of transforming it through holiness. The monks, by their prayer and example, intercede for the whole Church and society, embodying the call to holiness to which all Christians are summoned.

One notable letter addressed to Stagirius, a prominent advocate of asceticism, reveals John’s pastoral heart and his zeal for the sanctification of souls. In this letter, John emphasizes the vital role of the monastic life in the spiritual health of the Church, urging Stagirius to persevere amidst opposition and to serve as a model of humility and love.

John’s writings from this period also reveal a deep understanding of the dangers facing monks and clergy alike. He warns against the allure of worldly honors, the subtle temptations of self-righteousness, and the perils of laxity. His words call all who serve Christ to vigilance, humility, and charity, grounded in prayer and the sacraments.

Though cloistered within the monastery, John’s influence extended far beyond its walls. His letters were circulated among the faithful, inspiring many to embrace a life of greater devotion. His treatises became a source of spiritual nourishment and theological clarity, helping to dispel misunderstandings and to unite the Church around the ideal of holiness.

This period of literary and pastoral activity marked a critical stage in John’s preparation for the episcopal ministry. Through writing, he refined his theological vision and deepened his pastoral sensitivity, qualities that would distinguish his later preaching and governance.

Moreover, his works reflect the synthesis of ascetic zeal and pastoral charity that characterized his entire life. John Chrysostom was not content to live for himself alone; his monastic labors were directed toward the good of the Church and the salvation of souls.

In the silent cloisters, amid the prayers and manual labor, John’s soul grew in wisdom and grace. The works he produced stand as enduring testimonies of a life wholly dedicated to God and His people, a life that would soon burst forth into the wider arena of the Church’s struggles and triumphs.

Thus, the years of monastic seclusion were not years of idle retreat but a sacred preparation for the great ministry entrusted to him by the Lord. Through letters, treatises, and prayers, John Chrysostom’s voice began to echo beyond the monastery, calling all to holiness and fidelity to Christ.

Chapter VI: Ordination as Deacon—Description of Antioch—Works Composed During His Diaconate. A.D. 381–386

In the fullness of time, John Chrysostom was called forth from his life of monastic solitude into the service of the Church through ordination to the diaconate. This sacred step marked a new chapter in his pilgrimage, a transition from the hidden life of prayer to the active ministry among the faithful. Around the year 381, John was ordained a deacon, a ministry that would reveal both his spiritual gifts and his zeal for the salvation of souls.

Antioch, the great city where John had been born and educated, was now the scene of his ministry. Known for its splendor and bustling commerce, Antioch was also a city marked by spiritual ferment and social complexity. Its streets echoed with the voices of merchants, philosophers, and clergy, and the Church there was a vibrant but often troubled community.

The city’s religious life was marked by a diversity of beliefs and practices. Pagan temples still stood alongside Christian churches; the Jewish community was sizable and active; and heresies such as Arianism persisted despite imperial decrees against them. In this environment, the Church faced many challenges, and the need for strong and holy leadership was pressing.