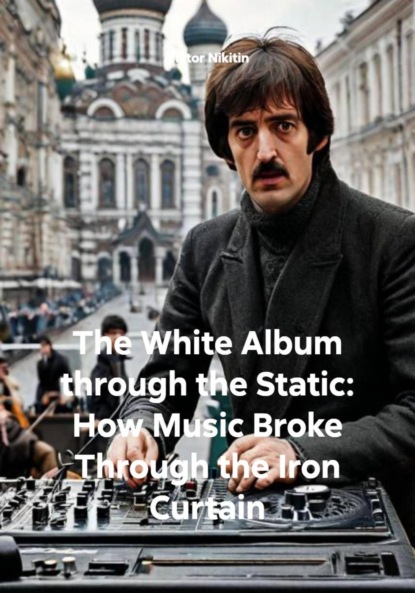

The White Album through the Static: How Music Broke Through the Iron Curtain

- -

- 100%

- +

The night of November 22, 1968, remains etched in my memory as one of the most vivid, quietly transformative, and almost sacred experiences of my youth. That evening, though outwardly unremarkable and cloaked in the familiar cold grayness of a late autumn in Moscow, felt charged with a subtle but profound significance that would linger with me for decades. The city outside was settling into the early chill of impending winter, its streets hushed beneath the pale glow of streetlamps, the distant sounds muffled by layers of snow and concrete, and within my cramped, dimly lit apartment, an atmosphere of hushed anticipation quietly took hold. The Beatles, who to much of the world represented a cultural revolution, had just released an album that was unlike anything before it—a self-titled double record, starkly known as the White Album due to its minimalist cover. To Western audiences, it was an event met with excitement, fanfare, and public celebration, with copies flooding record stores and radio stations playing it repeatedly. But for me, living in the tightly controlled environment of the Soviet Union, the arrival of this album was a fragile, near-mythical occurrence, an almost ghostly event. Unlike others who could hold the vinyl in their hands or listen to it on mainstream radio, I would only encounter this masterpiece as a fleeting, ghostly signal transmitted over shortwave radio frequencies. This signal had to fight a constant battle against the oppressive wall of government jamming – powerful electronic interference designed specifically to erase foreign voices and music from Soviet ears. This fragile, disrupted broadcast was my only connection to the White Album, making that night not just a memory of music but a symbol of cultural resistance, connection, and quiet hope.

More than just a casual recollection, that night was a sensory experience that continues to haunt the edges of my memory like a flickering film reel—every crackle of static, every distorted note, every fragile burst of melody etched as indelibly as the scent of warm vacuum tubes from my radio or the faint chill of November settling into the small, threadbare apartment where I sat alone. The city outside was itself a character in this scene, a sprawling, often gray, urban landscape caught between the fading warmth of autumn and the oncoming harshness of winter. The distant muffled sounds of traffic, footsteps, and the occasional bark of a dog blended with the muted hum of Soviet machinery, factory whistles, and the low murmur of a city that never fully slept but was always subdued by strict order. Inside, the small room I occupied became a cocoon of anticipation, a private theater where the boundary between my limited physical surroundings and the vast, unknown world beyond suddenly seemed to blur. The Beatles’ White Album was more than a new release—it was a crack in the Iron Curtain, an audible whisper of freedom and creativity reaching into a world that had been deliberately silenced. The stark white cover, devoid of imagery or color, symbolized a blank canvas, a mysterious and open invitation to explore new artistic terrain. To the Western world, the album’s arrival was an occasion for celebration and discourse, but for me, it was a fragile dream broadcast across hostile airwaves, vulnerable yet alive. Each note that made it through the crackling static was a small act of defiance against a regime determined to silence such voices, turning this night into a quiet revolution of sound and spirit.

Life in Moscow during those years was permeated by an ever-present sense of control and restriction, woven into the fabric of daily existence like the cold concrete buildings that surrounded me. The Soviet government exercised tight command over information flow, cultural expression, and even the smallest details of everyday life. Western music, particularly rock and roll, was viewed as a dangerous import—something capable of eroding the collective conformity and obedience demanded by the regime. The Beatles were not just musicians in this context; they were cultural icons who embodied freedom, creativity, and youthful rebellion—qualities that were threatening to the carefully maintained ideological order. Official channels rarely allowed their music to be heard, and owning a record by them was akin to possessing a forbidden artifact. Physical copies were extraordinarily rare, smuggled surreptitiously across borders, passed hand-to-hand in whispered exchanges, copied painstakingly onto cassette tapes with imperfect technology, and circulated in underground networks operating in the shadows of fear and secrecy. These networks became vital cultural lifelines, yet they were fragile and exposed. For most people in the Soviet Union, hearing the White Album as the artists intended was a distant dream, a rare luxury. It was within this environment of scarcity, secrecy, and censorship that I sought alternative ways to experience the music, yearning for a connection that transcended the limitations imposed on us.

The city itself was a fortress of conformity, built not only of steel and stone but of an invisible architecture of control and fear. Every radio station, every printed page, every cultural venue operated under the watchful eye of the state, which sought to mold its citizens’ minds as much as their daily routines. The streets of Moscow, while bustling and alive, seemed to echo with an unspoken tension—a mixture of hope and resignation, curiosity and caution. Against this backdrop, rock and roll music, especially that of the Beatles, took on an outsized significance. It was more than just entertainment; it was a symbol of freedom, of otherness, of a life not shackled by ideology and control. Yet this very power made it dangerous. The regime sought to stamp it out, to control its reach, to prevent it from stirring discontent or inspiring rebellion. Records were rare and precious commodities, smuggled in by travelers or black market dealers, then copied laboriously on primitive equipment, passed quietly from hand to hand in small, secret gatherings where the risk of discovery was ever-present. This underground culture was fragile but fiercely alive, a testament to the human desire for connection and expression that no regime could fully extinguish. Within this shadowy world, I found myself constantly searching for ways to access and preserve the music that was a lifeline to a larger, freer world beyond the walls that surrounded me.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «Литрес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на Литрес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.