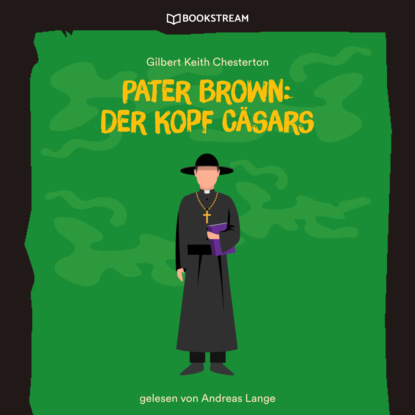

The Innocence of Father Brown / Неведение отца Брауна

Издательство:

Антология

Серия:

Abridged & AdaptedМетки:

приключенческие детективы,частное расследование,английские детективы,сборник рассказов,классическая Англия,психологические детективы,частные детективы,расследование преступлений,адаптированный английский,ограбления,знаменитые сыщики,литература Великобритании,Upper-Intermediate level,книги для чтения на английском языкеКниги этой серии:

Внешне неказистый и рассеянный, отец Браун ведёт привычную жизнь, пока не случается что-нибудь страшное. За его неприметной внешностью скрывается пытливый ум сыщика, способного разгадать непостижимые тайны. Откуда взялся труп незнакомца в саду знаменитого детектива? Кто мог убить известного поэта в запертой комнате? Кому удалось украсть сереебряные приборы на глазах у двенадцати свидетелей? На все вопросы отец Браун найдёт ответ. И ещё: он заботится не только о раскрытии дела, но и о спасении заблудших душ преступников. Даже к самым отпетым негодяям он пытается найти подход, стараясь смягчить их сердца и вызвать раскаяние.

Текст сокращён и адаптирован. Уровень B2.